Obama's narrative may unite his country but divide the world

Monday, 26.01.2009.

13:13

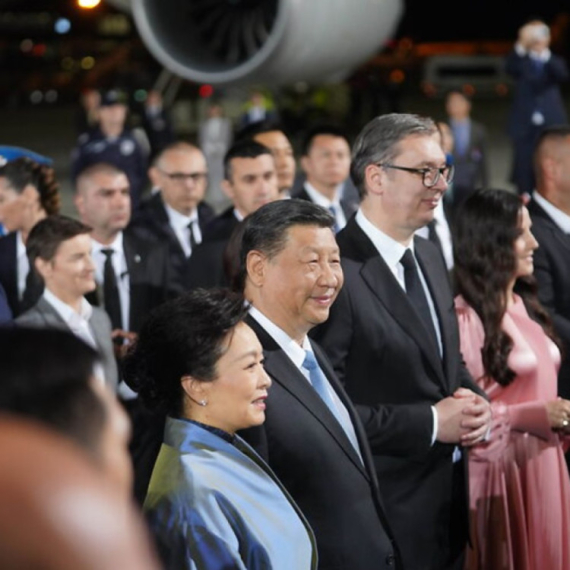

Obama's narrative may unite his country but divide the world The 47th president was sworn in on an unseasonably warm January day. President Gloria Evangelista, the first Hispanic and second woman president of the United States, took the oath on a Spanish-language bible held by her husband, Victor Chu. The controversy about Chu's lucrative lobbying contracts for Chinese companies was temporarily forgotten. Former president Barack Obama, his hair white since the traumatic last months of his second term in office, stood watching, sandwiched between his Republican predecessor, George Bush, and successor, Kitty McFarlane. The strange weather on this 20 January 2025 was attributed by many to the effects of global warming, which the Obama administration had vainly struggled to slow. In her inaugural speech, delivered partly in English and partly in Spanish, president Evangelista paid fulsome tribute to the Chinese-American strategic partnership, known colloquially as the G2. So much has been said to locate Obama's "historic" (oh weary moniker) inauguration day in the long sweep of American history, but we should also view it in the perspective of a probable future. According to the latest projection from the United States' own National Intelligence Council, "by 2025, the international system will be a global multipolar one with gaps in national power continuing to narrow between developed and developing countries". This does not require that America will decline; only that others continue to rise. There was a hint almost of melancholy defiance in Obama's inaugural rallying cry: "We remain the most prosperous, powerful nation on earth. We remain ..." In a speech that was very good, but not the overhyped Lincolnian great, President Obama spoke both to his country and to the world. I believe that he succeeded rhetorically and can succeed practically with the first audience, despite all the current difficulties, but I'm less sure about the second. In fact, there's a little-noted tension between the way he speaks to, for and about America, and the way he speaks to and about the world. The great theme of his whole life until now - including the literature we know he read most intensely, his own best book (Dreams from My Father) and his greatest speech so far (the Philadelphia speech on "race") - is the blending of multiple identities in an America that will finally be at one with itself. He not only is but consciously presents himself as the apotheosis of the American dream. He promises not merely to transcend, at long last, the United States' founding contradiction between liberty and slavery, but also to prepare America for a new order of ethnic diversity. His immediate family of Michelle and the girls already personify the first: every other day will bring some photograph of the black family in the White House. His almost encyclopedically diverse extended family, in which the languages spoken reportedly include Indonesian, French, Cantonese, German, Hebrew, Swahili, Luo and Igbo, represents the latter. As a wordsmith, he is adept at finding language to evoke this American blending of the many and the one. With time, I believe this sense of a more encompassing "we" can release significant new human energies among the less privileged members of American society. "Our patchwork heritage is a strength not a weakness," he said, and he can make it so. Although it was American financial follies, both private and public, that originally got us all into this mess, America is probably better placed than most European countries to get out of it. That may not seem fair, but whoever said life is fair? What's more, he can seize the chance of this crisis to make transformative investments in energy, education and infrastructure. So: the remaking of America? Yes, he can. Nothing in the future is certain, except death and taxes, but he has a better than sporting chance, especially if he is given a second term. But reshaping the world under renewed American leadership? Here I'm more sceptical. Things will surely be better than over the last eight years. That's hardly difficult. (Beside seeing the back of Bush, one of the frankly schadenfreudian delights of Tuesday's handover was to see former vice-president Dick Cheney trundle off looking more than ever, in his wheelchair, like Dr Strangelove.) Obama struck many notes that the world wants to hear from Washington, and struck them with characteristic grace. He spoke of the "tempering qualities of humility and restraint". He indicated some priorities: combatting nuclear proliferation and climate change, contributing more to development in "poor nations". He sent a special offer to "the Muslim world": a new way forward "based on mutual interest and mutual respect". The key passage was this: "And so to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman, and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more." Wonderful stuff; but the catch comes at the end. America may be ready to lead "once more" but what if the world is no longer ready to follow? What if it believes America has forfeited much of its moral right to lead over the last eight years, no longer has the power that it used to, and that anyway we are moving towards a global multipolar system, as Washington's own National Intelligence Council predicts? I am struck by how many little ifs and buts hedged even the customary welcoming words from world leaders. Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel offered warm and Christian congratulations, but added that "no single country can solve the problems of the world". Nicolas Sarkozy said: "We are eager for him to get to work so that with him we can change the world." (So, you see, France is ready to lead once more.) By the time we get to China, Russia, or an Arab world angered by Obama's silence over Gaza, the caveats come not as delicate barbs but as heavy artillery shells. You may say: but surely Obama, of all people, understands the full complexity of the world. I think that's right, and our great hope. At the same time, the story that he wants to tell the American people demands a reburnishing of traditional notions of American exceptionalism, mission and leadership. American patriotism, linked also to this idea of a mission to lead, is the glue with which he will bind his increasingly disparate nation together. The more disparate it is, the more glue you need. And this is not just instrumental. This story and this mission is also, so far as I can judge, one he himself believes in, for is not his own extraordinary personal journey proof positive of the story's truth and the mission's rightness? So there's a tension between the vision of revived Kennedyesque American leadership in the world that he unfolds to his own country, and what the rest of the world wants to hear or will now be ready to accept. A tension, I repeat, not an outright contradiction. How to manage that tension will be another of the many complex challenges facing this still youthful master of complexity. This article originally appeared on Guardian.co.uk Bush hugs Obama after the inauguration ceremony (Beta/AP) His chances of remaking America are good. Restoring US leadership in a multipolar global system will be harder. Timothy Garton Ash "Obama spoke both to his country and to the world. I believe that he succeeded rhetorically and can succeed practically with the first audience, despite all the current difficulties, but I'm less sure about the second."

Obama's narrative may unite his country but divide the world

The 47th president was sworn in on an unseasonably warm January day. President Gloria Evangelista, the first Hispanic and second woman president of the United States, took the oath on a Spanish-language bible held by her husband, Victor Chu. The controversy about Chu's lucrative lobbying contracts for Chinese companies was temporarily forgotten.Former president Barack Obama, his hair white since the traumatic last months of his second term in office, stood watching, sandwiched between his Republican predecessor, George Bush, and successor, Kitty McFarlane. The strange weather on this 20 January 2025 was attributed by many to the effects of global warming, which the Obama administration had vainly struggled to slow. In her inaugural speech, delivered partly in English and partly in Spanish, president Evangelista paid fulsome tribute to the Chinese-American strategic partnership, known colloquially as the G2.

So much has been said to locate Obama's "historic" (oh weary moniker) inauguration day in the long sweep of American history, but we should also view it in the perspective of a probable future. According to the latest projection from the United States' own National Intelligence Council, "by 2025, the international system will be a global multipolar one with gaps in national power continuing to narrow between developed and developing countries". This does not require that America will decline; only that others continue to rise. There was a hint almost of melancholy defiance in Obama's inaugural rallying cry: "We remain the most prosperous, powerful nation on earth. We remain ..."

In a speech that was very good, but not the overhyped Lincolnian great, President Obama spoke both to his country and to the world. I believe that he succeeded rhetorically and can succeed practically with the first audience, despite all the current difficulties, but I'm less sure about the second. In fact, there's a little-noted tension between the way he speaks to, for and about America, and the way he speaks to and about the world.

The great theme of his whole life until now - including the literature we know he read most intensely, his own best book (Dreams from My Father) and his greatest speech so far (the Philadelphia speech on "race") - is the blending of multiple identities in an America that will finally be at one with itself. He not only is but consciously presents himself as the apotheosis of the American dream. He promises not merely to transcend, at long last, the United States' founding contradiction between liberty and slavery, but also to prepare America for a new order of ethnic diversity. His immediate family of Michelle and the girls already personify the first: every other day will bring some photograph of the black family in the White House. His almost encyclopedically diverse extended family, in which the languages spoken reportedly include Indonesian, French, Cantonese, German, Hebrew, Swahili, Luo and Igbo, represents the latter.

As a wordsmith, he is adept at finding language to evoke this American blending of the many and the one. With time, I believe this sense of a more encompassing "we" can release significant new human energies among the less privileged members of American society. "Our patchwork heritage is a strength not a weakness," he said, and he can make it so. Although it was American financial follies, both private and public, that originally got us all into this mess, America is probably better placed than most European countries to get out of it. That may not seem fair, but whoever said life is fair? What's more, he can seize the chance of this crisis to make transformative investments in energy, education and infrastructure.

So: the remaking of America? Yes, he can. Nothing in the future is certain, except death and taxes, but he has a better than sporting chance, especially if he is given a second term. But reshaping the world under renewed American leadership? Here I'm more sceptical.

Things will surely be better than over the last eight years. That's hardly difficult. (Beside seeing the back of Bush, one of the frankly schadenfreudian delights of Tuesday's handover was to see former vice-president Dick Cheney trundle off looking more than ever, in his wheelchair, like Dr Strangelove.)

Obama struck many notes that the world wants to hear from Washington, and struck them with characteristic grace. He spoke of the "tempering qualities of humility and restraint". He indicated some priorities: combatting nuclear proliferation and climate change, contributing more to development in "poor nations". He sent a special offer to "the Muslim world": a new way forward "based on mutual interest and mutual respect".

The key passage was this: "And so to all other peoples and governments who are watching today, from the grandest capitals to the small village where my father was born: know that America is a friend of each nation and every man, woman, and child who seeks a future of peace and dignity, and we are ready to lead once more." Wonderful stuff; but the catch comes at the end. America may be ready to lead "once more" but what if the world is no longer ready to follow? What if it believes America has forfeited much of its moral right to lead over the last eight years, no longer has the power that it used to, and that anyway we are moving towards a global multipolar system, as Washington's own National Intelligence Council predicts?

I am struck by how many little ifs and buts hedged even the customary welcoming words from world leaders. Germany's chancellor Angela Merkel offered warm and Christian congratulations, but added that "no single country can solve the problems of the world". Nicolas Sarkozy said: "We are eager for him to get to work so that with him we can change the world." (So, you see, France is ready to lead once more.) By the time we get to China, Russia, or an Arab world angered by Obama's silence over Gaza, the caveats come not as delicate barbs but as heavy artillery shells.

You may say: but surely Obama, of all people, understands the full complexity of the world. I think that's right, and our great hope. At the same time, the story that he wants to tell the American people demands a reburnishing of traditional notions of American exceptionalism, mission and leadership. American patriotism, linked also to this idea of a mission to lead, is the glue with which he will bind his increasingly disparate nation together. The more disparate it is, the more glue you need. And this is not just instrumental. This story and this mission is also, so far as I can judge, one he himself believes in, for is not his own extraordinary personal journey proof positive of the story's truth and the mission's rightness?

So there's a tension between the vision of revived Kennedyesque American leadership in the world that he unfolds to his own country, and what the rest of the world wants to hear or will now be ready to accept. A tension, I repeat, not an outright contradiction. How to manage that tension will be another of the many complex challenges facing this still youthful master of complexity.

This article originally appeared on Guardian.co.uk

Komentari 2

Pogledaj komentare