Can Europe's Center Hold?

Friday, 18.03.2016.

13:00

Can Europe's Center Hold?

'Why did you come to Germany and not Italy?' I ask Jawad, a skinny, bright-eyed 16-year-old lad from Afghanistan, standing outside his family's blanket-tented six square metres of home at an emergency refugee reception centre in an East Berlin sports hall. Six months ago he spoke no German, but now he replies without hesitation: 'Italien hat kein Geld!'. Italy has no money! Short and to the point. A million Jawads arriving in a single year have so shaken up rich and bourgeois-liberal Germany that a xenophobic, anti-immigrant party has just won nearly a quarter of the vote in one East German state. Around the world people are asking: can Europe's centre hold?Politically and economically, Germany is the centre of Europe. The 'grand coalition' government of centre-right Christian Democrats and centre-left Social Democrats is the centre of Germany. And Angela Merkel is the centre of that centrist government. In a real sense, therefore, Merkel is the centre of Europe.

Faced with a bad result for her Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in regional elections in three federal states, she remains outwardly unmoved, sticking to her proclaimed EU-Turkish strategy which the EU summit is being asked to approve in Brussels today (Friday). Is this the patient, pragmatic steadiness that has won her so much trust? Or is it the hubris that sets in, as if by some law of physics, when a politician has been in power for more than 10 years? (Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl, Recep Tayyip Erdogan – the list goes on.)

As of now, the centre of German politics has held, but it is being eaten away at the edges like a papadom. Her coalition partner, the Social Democrats, also did badly in these elections, while the winners in the large and prosperous state of Baden-Württemberg were the Greens. Six parties now have to be taken seriously, or seven if you count separately the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU), which has been outspoken in its criticism of the Chancellor' s refugee policy. The journalist Stefan Kornelius suggests that the basic axis of German politics may be shifting from ' left-right' to ' centre-margins'. Mainstream politicians routinely refer to 'the democratic parties' to distinguish them from the far-left Linke and now the anti-immigrant, anti-Euro Alternative for Germany (AfD).

The electoral success of AfD has been the cover story around the world. Some of its candidates said horrendous things. One Michael Ahlborn, in the East German state of Saxony-Anhalt, called the Turks a Drecksvolk, a shit-people. Günter Lenhardt, an NCO in the military reserve and party candidate in Baden-Württemberg, said 'for the refugee it surely makes no difference at which frontier – the Greek or the German – he dies'. But these comments, close to the rhetoric of the far-right, xenophobic Pegida, may blind us to the real challenge. Everyone I talked to during an intensive week in Berlin agreed that a striking feature of AfD is the support it enjoys among the educated middle class: professors, doctors, entrepreneurs, lawyers, people who know exactly when to say 'Frau Doktor' and are themselves often 'Herr Doktor', if not 'Herr Professor'.

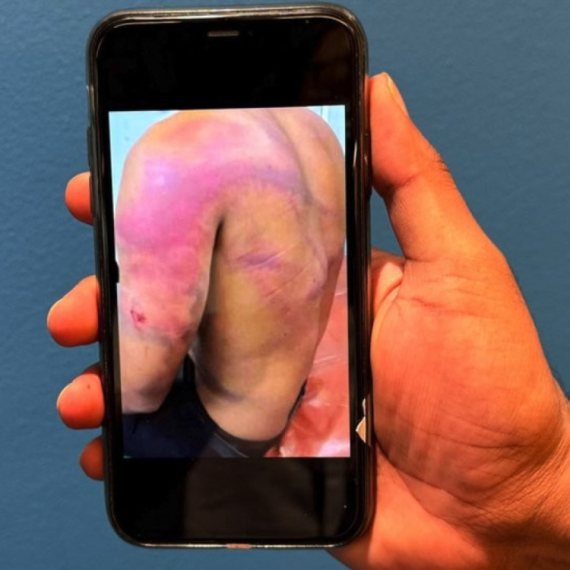

To counter this radicalisation and fragmentation, the centre – and the centre of the centre, a.k.a. Merkel – needs to do two very demanding things: demonstrate to the millions of Germans who doubt it that Germany can successfully integrate more than a million newcomers with a very different cultural background, and, secondly, stem the flow of new arrivals. For the former, a visit to a refugee centre shows just what an extraordinary effort of civilised public hospitality this country is making (6 square metres for everyone, the Berlin reception centre supervisor tells me, food, clothing, medical care, special school classes, a monthly sum paid into a bank account), but also how the numbers are straining state capacity and public patience to breaking point.

Stemming the flow, even if all goes according to Merkel's plan, means an alarming dependence on two erratic and undemocratic rulers, Erdogan and Vladimir Putin – the sultan and the tsar. To maintain Germany's fundamentally ethical and humane openness to genuine refugees, Merkel has supported a proposal that is both ethically and legally problematic: herd refugees into camps in Greece and then make a 'one for one' swap with Syrian refugees in Turkey. This also means the EU embracing the Turkish sultan even as he is trampling press freedom underfoot and otherwise violating human rights and European standards. Beyond that, it means depending on Putin's Russia to keep alive the perilous 'cessation of hostilities' in Syria. Talking to people close to the Chancellor, it is painfully clear that their whole policy hangs on these Turkish and Russian threads. The word Überrealpolitik has been used to describe it but, as with all 'realism' in foreign policy, one has to ask 'how realistic is it?' And this is before we even get to the likelihood of many more refugees making the life-threatening sea crossing from Libya to Italy, or by other routes.

The refugee crisis currently dominates German politics, but it is only one of several crises that assail Europe's central power. There's also the euro crisis, low-level armed conflict and high-level corruption in Ukraine, a conservative nationalist government in neighbouring Poland, Marine le Pen in France – oh yes, and the threat of Brexit. They really don't want Britain to leave but it's not top of their agenda. If we Brits do vote for Brexit, they won't offer Britain a more favourable deal but will turn at once to France, aiming to build a strong European core. If the self-styled island nation won't help the rest of Europe, it will have to fend for itself. The Germans have serious work to do: a country to restabilise and a continent with it.

Timothy Garton Ash is Professor of European Studies at Oxford University, where he currently leads the freespeechdebate project, and a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. His new book Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World will be published next spring

Komentari 0