Hungary: Hints of “Greater Hungary”

Monday, 03.05.2010.

11:06

Hungary: Hints of “Greater Hungary” This plan could be seen as a step to ensure greater security for Hungary should its current protectors — the European Union and NATO — weaken. Because of the history and geography of Central Europe, the plan could make Hungary’s neighbors nervous. Hungarian President Laszlo Solyom on April 28 proposed to make the leader of the center-right Fidesz party the country’s next prime minister. Fidesz won a two-thirds majority in the second round of general elections April 25. The win gives Fidesz leader Viktor Orban one of the largest democratically won mandates in post-World War II Europe. With that win comes considerable power, including the ability to change the constitution without consulting other parties. And while Fidesz’s plans to cut the bureaucracy, lower the tax rate and renegotiate the terms of the International Monetary Fund’s 20-billion-euro ($26.6 billion) aid package are receiving more attention in the global media, STRATFOR considers more politically relevant that Fidesz wants to grant citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living in countries bordering Hungary — or 2.5 million people, with the largest concentrations in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia. The plan to give ethnic Hungarians in neighboring nations Hungarian passports can be perceived as an insurance policy — a way of broadening its power and securing itself should its protectors, the European Union and NATO, weaken. From Hungary’s neighbors’ perspective, the plan is contentious due to the region’s history and geography. Viktor Orban (Beta/AP) The geopolitics of Hungary The Hungarian heartland lies in the fertile Pannonian plain between the Danube River and the Carpathian Mountains — the Hortobagy region in present-day eastern Hungary. From this heartland — relatively defenseless in the middle of Central Europe — Hungary has throughout its history sought to extend its territory to natural barriers for protection: the Carpathians in the east and northeast, the Tatra Mountains in the north, the foothills of the Austrian Alps (known as Burgenland) to the west and the defensive barrier on the Sava-Danube line in the south. With these efforts, populations moved into the regions that abutted the major mountain chains and rivers forming the boundaries of the Hungarian state. These ethnic Hungarians, along with more than 70 percent of the Kingdom of Hungary’s pre-1918 territory, were lost after World War I. Allied powers sought to reduce Austria and Hungary — allies of Germany — and surround them with territorially larger countries that would purportedly keep them in check. In 1920, the Treaty of Trianon carved up Hungarian territory and created the countries of Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later called Yugoslavia). These new countries all harbored resentment toward Hungarians, who had ruled them intermittently for centuries by Budapest. Allied powers expected the Hungarian minorities in these new countries to eventually move back into “Trianon Hungary,” not survive discrimination and retribution, as they did. Hungarians still consider the Treaty of Trianon a national tragedy. Besides damaging national pride, the treaty also left Budapest defenseless on the Pannonian plain. Between 1920 and 1940, Hungary prepared to revise what it perceived as the injustices of Trianon, recover its lost populations and reach its geographic barriers, especially in the Tatra Mountains and the Carpathians. Budapest allied with the Axis powers right before World War II in large part to do exactly that, pushing its borders into neighboring countries aggressively (see map at left). However, it found itself on the losing side again and fell into the Soviet sphere at the end of the war, establishing Trianon Hungary to this day. Hungary today Only one Hungarian political party — the ultra-right Jobbik party, which received 17 percent of the votes in the last elections — has a political platform that includes trying to revise Trianon. Otherwise, it is not a serious political priority in Hungary. Budapest’s security is entrenched in its alliances with the European Union and NATO, and attempting to revise its borders would therefore seriously undermine its security. Budapest would essentially become what Belgrade was in the1990s — ostracized by Western alliances. However, if the alliances that provide the geographically vulnerable Hungary with security were somehow weakened, Budapest would need guarantees that it is not isolated on the Pannonian plain without traditional buffers. With NATO member states maintaining divergent policies toward a resurgent Russia and the European Union mired in its greatest institutional crisis yet, the security and political architecture of post-World War II Europe has never looked more uncertain. This is not to say that the European Union and NATO are on the brink of collapse, but post-communist EU member states are nervously watching France and Germany’s lack of resistance to Russia’s reconsolidation of the former Soviet sphere and their general lack of sympathy for Central and Eastern Europe’s (as well as Greece’s) economic problems. Amid these fluctuating circumstances, Fidesz’s plan to give Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries citizenship can be perceived through the lens of geopolitics as an insurance policy against a potentially more uncertain future. Of course, just as Hungary may perceive ethnic Hungarians as an insurance policy, its neighbors would perceive them as a liability — more so as the security and economic alliances on the Continent become more tenuous. Recent comments from Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico confirm this nervousness, which will undoubtedly be emulated in Romania and Serbia. Bucharest and Belgrade are no strangers to using ethnic minorities outside their borders for geopolitical gain. Romania has aggressively given Moldavians Romanian passports in an effort to wrest Moldova from Russia’s control, and Serbia used its minorities in neighboring ex-Yugoslav republics during the wars of the 1990s. Familiarity with such policies will only fuel greater concern for Bucharest and Belgrade. Tensions are therefore likely to rise in Central Europe, particularly if evidence continues to mount that the NATO and EU alliances are in some way less definitive guarantees. This report is republished with permission of STRATFOR The center-right Hungarian party Fidesz won a two-thirds majority in elections held April 25. The mandate gives Fidesz considerable power to carry out its plans, including granting citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living in neighboring countries. STRATFOR "This plan could be seen as a step to ensure greater security for Hungary should its current protectors — the European Union and NATO — weaken. Because of the history and geography of Central Europe..."

Hungary: Hints of “Greater Hungary”

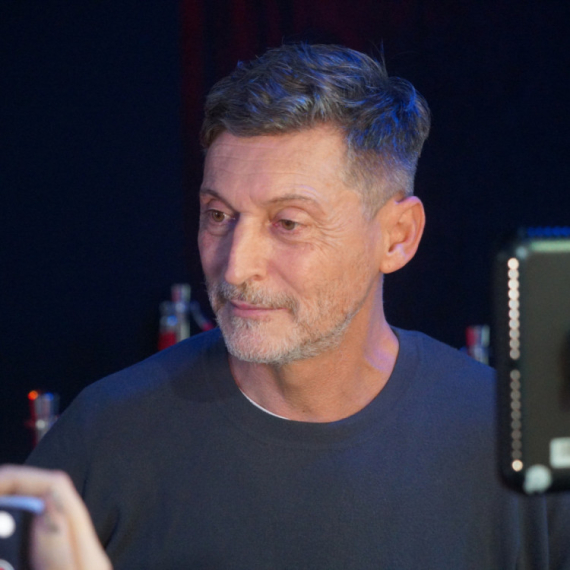

This plan could be seen as a step to ensure greater security for Hungary should its current protectors — the European Union and NATO — weaken. Because of the history and geography of Central Europe, the plan could make Hungary’s neighbors nervous.Hungarian President Laszlo Solyom on April 28 proposed to make the leader of the center-right Fidesz party the country’s next prime minister. Fidesz won a two-thirds majority in the second round of general elections April 25. The win gives Fidesz leader Viktor Orban one of the largest democratically won mandates in post-World War II Europe. With that win comes considerable power, including the ability to change the constitution without consulting other parties.

And while Fidesz’s plans to cut the bureaucracy, lower the tax rate and renegotiate the terms of the International Monetary Fund’s 20-billion-euro ($26.6 billion) aid package are receiving more attention in the global media, STRATFOR considers more politically relevant that Fidesz wants to grant citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living in countries bordering Hungary — or 2.5 million people, with the largest concentrations in Romania, Slovakia and Serbia.

The plan to give ethnic Hungarians in neighboring nations Hungarian passports can be perceived as an insurance policy — a way of broadening its power and securing itself should its protectors, the European Union and NATO, weaken. From Hungary’s neighbors’ perspective, the plan is contentious due to the region’s history and geography.

The geopolitics of Hungary

The Hungarian heartland lies in the fertile Pannonian plain between the Danube River and the Carpathian Mountains — the Hortobagy region in present-day eastern Hungary. From this heartland — relatively defenseless in the middle of Central Europe — Hungary has throughout its history sought to extend its territory to natural barriers for protection: the Carpathians in the east and northeast, the Tatra Mountains in the north, the foothills of the Austrian Alps (known as Burgenland) to the west and the defensive barrier on the Sava-Danube line in the south. With these efforts, populations moved into the regions that abutted the major mountain chains and rivers forming the boundaries of the Hungarian state.These ethnic Hungarians, along with more than 70 percent of the Kingdom of Hungary’s pre-1918 territory, were lost after World War I. Allied powers sought to reduce Austria and Hungary — allies of Germany — and surround them with territorially larger countries that would purportedly keep them in check. In 1920, the Treaty of Trianon carved up Hungarian territory and created the countries of Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later called Yugoslavia). These new countries all harbored resentment toward Hungarians, who had ruled them intermittently for centuries by Budapest. Allied powers expected the Hungarian minorities in these new countries to eventually move back into “Trianon Hungary,” not survive discrimination and retribution, as they did.

Hungarians still consider the Treaty of Trianon a national tragedy. Besides damaging national pride, the treaty also left Budapest defenseless on the Pannonian plain. Between 1920 and 1940, Hungary prepared to revise what it perceived as the injustices of Trianon, recover its lost populations and reach its geographic barriers, especially in the Tatra Mountains and the Carpathians. Budapest allied with the Axis powers right before World War II in large part to do exactly that, pushing its borders into neighboring countries aggressively (see map at left). However, it found itself on the losing side again and fell into the Soviet sphere at the end of the war, establishing Trianon Hungary to this day.

Hungary today

Only one Hungarian political party — the ultra-right Jobbik party, which received 17 percent of the votes in the last elections — has a political platform that includes trying to revise Trianon. Otherwise, it is not a serious political priority in Hungary. Budapest’s security is entrenched in its alliances with the European Union and NATO, and attempting to revise its borders would therefore seriously undermine its security. Budapest would essentially become what Belgrade was in the1990s — ostracized by Western alliances.However, if the alliances that provide the geographically vulnerable Hungary with security were somehow weakened, Budapest would need guarantees that it is not isolated on the Pannonian plain without traditional buffers. With NATO member states maintaining divergent policies toward a resurgent Russia and the European Union mired in its greatest institutional crisis yet, the security and political architecture of post-World War II Europe has never looked more uncertain. This is not to say that the European Union and NATO are on the brink of collapse, but post-communist EU member states are nervously watching France and Germany’s lack of resistance to Russia’s reconsolidation of the former Soviet sphere and their general lack of sympathy for Central and Eastern Europe’s (as well as Greece’s) economic problems.

Amid these fluctuating circumstances, Fidesz’s plan to give Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries citizenship can be perceived through the lens of geopolitics as an insurance policy against a potentially more uncertain future. Of course, just as Hungary may perceive ethnic Hungarians as an insurance policy, its neighbors would perceive them as a liability — more so as the security and economic alliances on the Continent become more tenuous. Recent comments from Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico confirm this nervousness, which will undoubtedly be emulated in Romania and Serbia.

Bucharest and Belgrade are no strangers to using ethnic minorities outside their borders for geopolitical gain. Romania has aggressively given Moldavians Romanian passports in an effort to wrest Moldova from Russia’s control, and Serbia used its minorities in neighboring ex-Yugoslav republics during the wars of the 1990s. Familiarity with such policies will only fuel greater concern for Bucharest and Belgrade. Tensions are therefore likely to rise in Central Europe, particularly if evidence continues to mount that the NATO and EU alliances are in some way less definitive guarantees.

This report is republished with permission of STRATFOR

Komentari 2

Pogledaj komentare