Europe, wake up!

Saturday, 22.05.2010.

13:45

Europe, wake up! Power shifts to Asia. The historical motors of European integration are either lost or spluttering. European leaders rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic, while lecturing the rest of the world on ocean navigation. The crisis of the eurozone has only just begun. The bond markets have not been convinced even by last week's giant 'shock and awe' bail-out of Greece. The one thing that moved them was the European Central Bank's readiness to start buying eurozone government bonds; but it still costs multiples more for the Greek or Portugese government to borrow than it does for the German government. A leading bond strategist tells me he now sees two alternatives: either the eurozone moves towards a fiscal union, with a further loss of sovereignty by member states and drastic deficit reduction imposed by this external constraint, or some of the weaker member states default, either inside the eurozone or by leaving it altogether. At which point capital flees, even more than it has already, from the weak to the strong: that is, from the eurozone to elsewhere and, within today's eurozone, to Germany. The domestic and international politics of both these paths are bloody. (In Greece, already literally so.) The tensions within European societies will rise, but so will those between European states. In particular, resentments within and towards Germany, the continent's central power, are bound to increase either way: if Germany imposes tough terms for a fiscal union, while at the same time underwriting other governments' risk, or if it lets a Greece or Portugal go to the wall, resulting in further capital flight to Germany. In the very best case, if the old 'challenge and response' pattern of integration-through-crisis works once again, Europe will be preoccupied with resolving its internal economic and financial problems for years to come. The current and emerging great powers of the 21st century, from the United States and China to Brazil and Russia, already treat European pretensions to be a major single player on the world stage with something close to contempt. The minimal deal at last year's Copenhagen summit on climate change, a subject on which Europe claims to lead, was reached between the US, China, India, South Africa and Brazil. Europe was not even in the room. Copenhagen was a wake-up call to which Europe failed to awake. The two figures the EU has chosen to represent it on the world stage are almost entirely unknown outside Europe. At a recent meeting at St Antony's College in the University of Oxford, the New York Times' foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman quipped that he wouldn't know the president of the European Council 'even if he sat on my lap'. The EU's new High Representative for foreign and security policy, Catherine Ashton, may turn out to be an effective bureaucratic operator in Brussels, but talking to officials there one understands just how difficult the business of building a European foreign service will be. Beijing, Moscow, New Delhi and Washington are not waiting with bated breath. For them, life is elsewhere. Barack Obama's United States is preoccupied with nation-building at home, then with the wider Middle East and China. Britain's new prime minister earns a phone call from the president, and a flattering reference to the 'special relationship', but Obama has no sentimental attachment to the old continent. His question to Europe is: 'what can you do for us today?' The new geometries of world power are described by acronyms like BASICs (Brazil, South Africa, India, China), BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China) and IBSA (India, Brazil, South Africa). Some of this is anticipating future developments, which may not happen, but in the market of geopolitics, as in financial markets, expectations are also realities. The European Union is still the world's largest economy. It has enormous resources of hard and soft power, currently much bigger than those of the emerging great powers. But the trend is against it, and it punches far below its weight. If it still wants to shape the world, in the interests of its citizens, then it must close the gap between its potential and its actual power. It's not doing so. Why? For more than fifty years after 1945, there were five great driving forces of the European project. They were: the memory of war, a deeply motivating personal memory well into the generation of Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterand; the Soviet threat to western Europe, and the desire of central and east European peoples to escape from Soviet domination into freedom and security; American support for European integration, in response to the Soviet threat; the Federal Republic of Germany, wanting to rehabilitate post-Nazi Germany in the European family and also to win its European neighbours' support for German unification; and France, with its dual-purpose ambition for a French-led Europe. All five driving forces are now either gone or greatly weakened. Instead, we have a set of new rationales for the project. They include global challenges, such as climate change and the globalised financial system, which increasingly impact directly on the lives of our citizens, and the emerging great powers of a multi-polar world. In a world of giants, it helps to be a giant yourself. But a rationale, an intellectual argument, is not the same as an emotional driving force, based on direct personal experience and an immediate sense of threat. We don't have that sense in today's Europe. For standard of living and quality of life, most Europeans have never had it so good. They don't realise how radically things need to change in order that things may remain the same. It would take a new Winston Churchill to explain this to all Europeans, in the poetry of 'blood, sweat and tears'. Instead, we have Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, Silvio Berlusconi, and now David Cameron. Britain's new liberal conservative coalition government is making an encouragingly constructive start in Europe. On Tuesday, the country's new Chancellor of the Exchequer [finance minister] George Osborne swallowed the proposed hedge fund directive in Brussels with all the grace of a Victorian English traveller eating a dish of sheep's eyes in a Bedouin tent. (The British government still hopes to get the directive modified in the European parliament.) Today and tomorrow, Cameron is dedicating his first overseas trip as prime minister to his new colleagues in Paris and Berlin. But even if Britain is not going to be the European brake that most Conservative Mps want it to be, it will hardly be the motor. Where, then, is the dynamism to come from? I do not know. I do not see it. Yes, we have been through many bouts of europessimism before; for as long as I can remember there have been such bouts. Every time Europe has somehow got out of the dumps, to take another step forward. Europe's global competitors all have big problems of their own. In ten years' time, historians may yet look back and laugh at the europessimism of 2010. But only if Europe now wakes up to the world we're in. Europe, wake up! timothygartonash.com Protestors in Berlin (Beta/AP) Can anyone save me from europessimism? I feel more depressed about the state of the European project than I have for decades. The eurozone is in mortal danger. European foreign policy is advancing at the pace of a drunken snail. Timothy Garton Ash "In ten years' time, historians may yet look back and laugh at the europessimism of 2010. But only if Europe now wakes up to the world we're in."

Europe, wake up!

Power shifts to Asia. The historical motors of European integration are either lost or spluttering. European leaders rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic, while lecturing the rest of the world on ocean navigation.The crisis of the eurozone has only just begun. The bond markets have not been convinced even by last week's giant 'shock and awe' bail-out of Greece. The one thing that moved them was the European Central Bank's readiness to start buying eurozone government bonds; but it still costs multiples more for the Greek or Portugese government to borrow than it does for the German government.

A leading bond strategist tells me he now sees two alternatives: either the eurozone moves towards a fiscal union, with a further loss of sovereignty by member states and drastic deficit reduction imposed by this external constraint, or some of the weaker member states default, either inside the eurozone or by leaving it altogether. At which point capital flees, even more than it has already, from the weak to the strong: that is, from the eurozone to elsewhere and, within today's eurozone, to Germany.

The domestic and international politics of both these paths are bloody. (In Greece, already literally so.) The tensions within European societies will rise, but so will those between European states. In particular, resentments within and towards Germany, the continent's central power, are bound to increase either way: if Germany imposes tough terms for a fiscal union, while at the same time underwriting other governments' risk, or if it lets a Greece or Portugal go to the wall, resulting in further capital flight to Germany. In the very best case, if the old 'challenge and response' pattern of integration-through-crisis works once again, Europe will be preoccupied with resolving its internal economic and financial problems for years to come.

The current and emerging great powers of the 21st century, from the United States and China to Brazil and Russia, already treat European pretensions to be a major single player on the world stage with something close to contempt. The minimal deal at last year's Copenhagen summit on climate change, a subject on which Europe claims to lead, was reached between the US, China, India, South Africa and Brazil. Europe was not even in the room.

Copenhagen was a wake-up call to which Europe failed to awake. The two figures the EU has chosen to represent it on the world stage are almost entirely unknown outside Europe. At a recent meeting at St Antony's College in the University of Oxford, the New York Times' foreign affairs columnist Thomas Friedman quipped that he wouldn't know the president of the European Council 'even if he sat on my lap'. The EU's new High Representative for foreign and security policy, Catherine Ashton, may turn out to be an effective bureaucratic operator in Brussels, but talking to officials there one understands just how difficult the business of building a European foreign service will be.

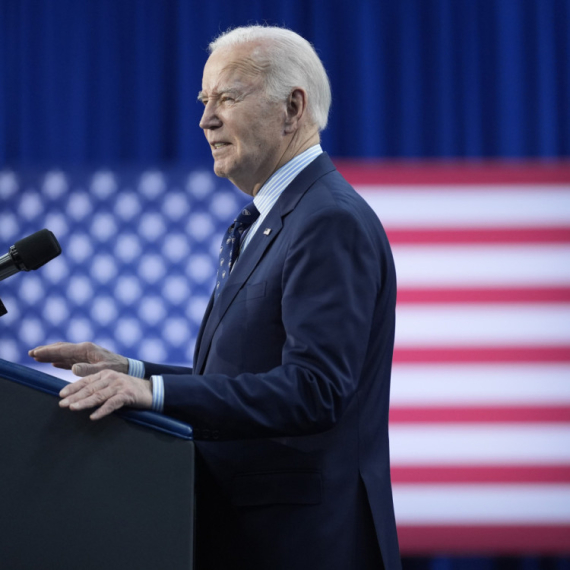

Beijing, Moscow, New Delhi and Washington are not waiting with bated breath. For them, life is elsewhere. Barack Obama's United States is preoccupied with nation-building at home, then with the wider Middle East and China. Britain's new prime minister earns a phone call from the president, and a flattering reference to the 'special relationship', but Obama has no sentimental attachment to the old continent. His question to Europe is: 'what can you do for us today?' The new geometries of world power are described by acronyms like BASICs (Brazil, South Africa, India, China), BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China) and IBSA (India, Brazil, South Africa).

Some of this is anticipating future developments, which may not happen, but in the market of geopolitics, as in financial markets, expectations are also realities.

The European Union is still the world's largest economy. It has enormous resources of hard and soft power, currently much bigger than those of the emerging great powers. But the trend is against it, and it punches far below its weight. If it still wants to shape the world, in the interests of its citizens, then it must close the gap between its potential and its actual power. It's not doing so. Why?

For more than fifty years after 1945, there were five great driving forces of the European project. They were: the memory of war, a deeply motivating personal memory well into the generation of Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterand; the Soviet threat to western Europe, and the desire of central and east European peoples to escape from Soviet domination into freedom and security; American support for European integration, in response to the Soviet threat; the Federal Republic of Germany, wanting to rehabilitate post-Nazi Germany in the European family and also to win its European neighbours' support for German unification; and France, with its dual-purpose ambition for a French-led Europe. All five driving forces are now either gone or greatly weakened.

Instead, we have a set of new rationales for the project. They include global challenges, such as climate change and the globalised financial system, which increasingly impact directly on the lives of our citizens, and the emerging great powers of a multi-polar world. In a world of giants, it helps to be a giant yourself. But a rationale, an intellectual argument, is not the same as an emotional driving force, based on direct personal experience and an immediate sense of threat. We don't have that sense in today's Europe. For standard of living and quality of life, most Europeans have never had it so good. They don't realise how radically things need to change in order that things may remain the same.

It would take a new Winston Churchill to explain this to all Europeans, in the poetry of 'blood, sweat and tears'. Instead, we have Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, Silvio Berlusconi, and now David Cameron. Britain's new liberal conservative coalition government is making an encouragingly constructive start in Europe.

On Tuesday, the country's new Chancellor of the Exchequer [finance minister] George Osborne swallowed the proposed hedge fund directive in Brussels with all the grace of a Victorian English traveller eating a dish of sheep's eyes in a Bedouin tent. (The British government still hopes to get the directive modified in the European parliament.) Today and tomorrow, Cameron is dedicating his first overseas trip as prime minister to his new colleagues in Paris and Berlin. But even if Britain is not going to be the European brake that most Conservative Mps want it to be, it will hardly be the motor.

Where, then, is the dynamism to come from? I do not know. I do not see it. Yes, we have been through many bouts of europessimism before; for as long as I can remember there have been such bouts. Every time Europe has somehow got out of the dumps, to take another step forward. Europe's global competitors all have big problems of their own. In ten years' time, historians may yet look back and laugh at the europessimism of 2010. But only if Europe now wakes up to the world we're in.

Europe, wake up!

timothygartonash.com

Komentari 3

Pogledaj komentare