Croatian genocide lawsuit opens

Proceedings have begun at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Croatia’s lawsuit against Serbia for genocide committed during the 1991-1995 war.

Monday, 26.05.2008.

11:10

Proceedings have begun at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Croatia’s lawsuit against Serbia for genocide committed during the 1991-1995 war. The hearing is scheduled to last for five days, and will deal exclusively with the court’s jurisdiction. Croatian genocide lawsuit opens Croatia instituted proceedings against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SRJ) in 1999 for the alleged genocide that took place between 1991 and 1995. Serbia’s legal team will argue that the ICJ does not have jurisdiction in this case since Serbia, as Yugoslavia’s successor state, was not a member of the United Nations, nor had it signed the Convention on Genocide on which the court’s jurisdiction is based, at the time that Croatia’s suit was filed. Head of the Serbian legal team Tibor Varadi said that serious crimes had been committed in Croatia, but not genocide. He said that the court did not have the jurisdiction over the Croatian case because at the time the charges were filed, in 1999, Yugoslavia had neither been a UN member nor a signatory of the Genocide Convention, which was an essential condition for trying the case at the UN’s highest court. “Therefore, looking into the events in Croatia at that time is not the role of this court,” he said, adding that on the same basis, the International Court of Justice had decided in 2004 that it had no jurisdiction over Belgrade’s charges against NATO member-states for the illegal use of force in 1999. “There were perpetrators and victims of crimes on all sides, but what happened never reached the level of genocide,” Varadi said, adding that the Hague Tribunal had not even accused anyone of genocide in Croatia. As an example of crimes against Serbs in Croatia, Varadi cited Operation Storm, quoting UNHCR statistics that “in the largest single exodus” in the summer of 1995, 180,000 Serbs were forced out of the country. Varadi also cited the testimony of then U.S. Ambassador to Croatia Peter Galbraith in the trial of Slobodan Milosevic before the Hague Tribunal, where he said that Croatian forces had behaved “criminally” during Storm, torching Serb property and killing civilians, and that then Croatian President Franjo Tudjman had not allowed Serbs to return. He said that Serbia’s intention was not to deny the suffering of the Croatian people described in the charges, or to claim Serbs were not responsible for that suffering, because “these crimes were committed,” and the victims deserved respect. “That does not mean that these crimes can be called genocide,” said the head of the Serbian legal team. Since the end of the war, relations between Serbia and Croatia, who share the same vision of a future in the EU, had returned to normal, and that called for reconciliation with the past and punishing individuals who had committed war crimes, he said. Varadi said that President Boris Tadic had publicly apologized to the Croatian people for all the suffering that Serbian citizens had inflicted on them, and that trials were ongoing in Belgrade for war crimes in Ovcara and the Slavonian village of Lovas, adding that Serbia had returned cultural property to Croatia. The other two members of Serbia's legal team in the case are Vladimir Djeric and Andreas Zimmerman, a professor from Berlin.

Croatian genocide lawsuit opens

Croatia instituted proceedings against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SRJ) in 1999 for the alleged genocide that took place between 1991 and 1995.Serbia’s legal team will argue that the ICJ does not have jurisdiction in this case since Serbia, as Yugoslavia’s successor state, was not a member of the United Nations, nor had it signed the Convention on Genocide on which the court’s jurisdiction is based, at the time that Croatia’s suit was filed.

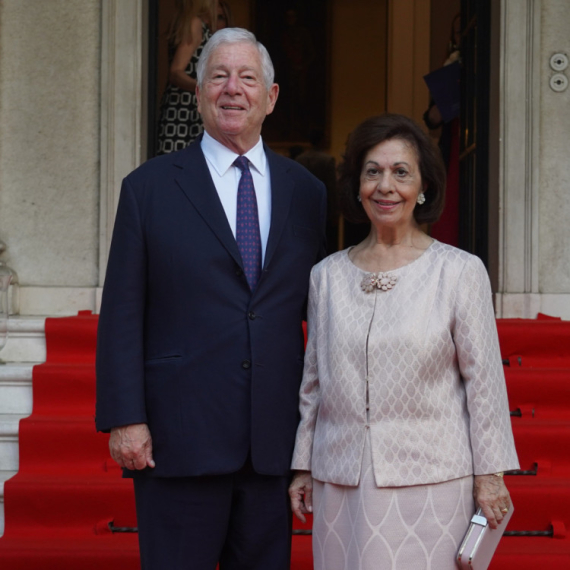

Head of the Serbian legal team Tibor Varadi said that serious crimes had been committed in Croatia, but not genocide.

He said that the court did not have the jurisdiction over the Croatian case because at the time the charges were filed, in 1999, Yugoslavia had neither been a UN member nor a signatory of the Genocide Convention, which was an essential condition for trying the case at the UN’s highest court.

“Therefore, looking into the events in Croatia at that time is not the role of this court,” he said, adding that on the same basis, the International Court of Justice had decided in 2004 that it had no jurisdiction over Belgrade’s charges against NATO member-states for the illegal use of force in 1999.

“There were perpetrators and victims of crimes on all sides, but what happened never reached the level of genocide,” Varadi said, adding that the Hague Tribunal had not even accused anyone of genocide in Croatia.

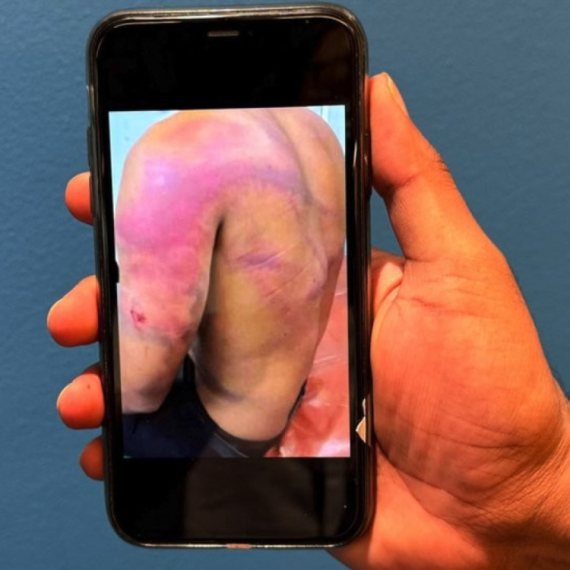

As an example of crimes against Serbs in Croatia, Varadi cited Operation Storm, quoting UNHCR statistics that “in the largest single exodus” in the summer of 1995, 180,000 Serbs were forced out of the country.

Varadi also cited the testimony of then U.S. Ambassador to Croatia Peter Galbraith in the trial of Slobodan Milošević before the Hague Tribunal, where he said that Croatian forces had behaved “criminally” during Storm, torching Serb property and killing civilians, and that then Croatian President Franjo Tuđman had not allowed Serbs to return.

He said that Serbia’s intention was not to deny the suffering of the Croatian people described in the charges, or to claim Serbs were not responsible for that suffering, because “these crimes were committed,” and the victims deserved respect.

“That does not mean that these crimes can be called genocide,” said the head of the Serbian legal team.

Since the end of the war, relations between Serbia and Croatia, who share the same vision of a future in the EU, had returned to normal, and that called for reconciliation with the past and punishing individuals who had committed war crimes, he said.

Varadi said that President Boris Tadić had publicly apologized to the Croatian people for all the suffering that Serbian citizens had inflicted on them, and that trials were ongoing in Belgrade for war crimes in Ovčara and the Slavonian village of Lovas, adding that Serbia had returned cultural property to Croatia.

The other two members of Serbia's legal team in the case are Vladimir Đerić and Andreas Zimmerman, a professor from Berlin.

Komentari 12

Pogledaj komentare