"Serbs and Albanians lived not as neighbors, but together"

Monday, 19.06.2017.

15:40

"Serbs and Albanians lived not as neighbors, but together"

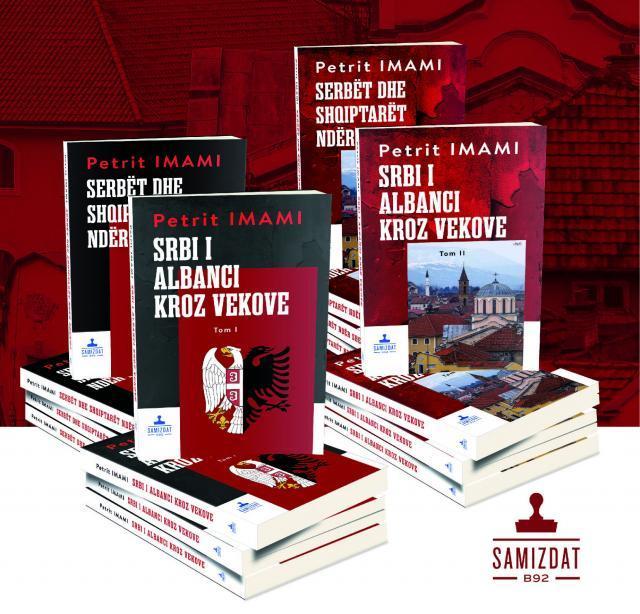

"The need to write the book 'Serbs and Albanians Through Centuries' arose in me from the deep motive to face the history of the two peoples who have lived in the neighborhood for over a thousand years. I was curious to know their relationships: what they have been, what brought them together, and what distanced them from one another; what led to friendships and to hostilities. I tried to cover internal and external flows in the historical vertical that have influenced the actions of their members, leaders and ordinary people," the author, Petrit Imami, said during the promotion of the book, published by Samizdat B92.Now comes the first review, written for Koha Ditore by Aleksandar Pavlovic.

Petrit Imami's "Serbs and Albanians Through Centuries" represents a multiple-times reworked, revised and expanded edition of the book published twenty years ago. It is interesting to recall that the first edition was published in 1998, during fierce clashes in Kosovo, and that the police then raided the publisher, Samizdat B92, and seized virtually the entire print run. The book, however, appeared two years later, after Milosevic's fall, in its known, previous edition, that already contained some additions and corrections compared to the first one from 1998.

This new edition is at least twice as long as the previous one, and is divided into three volumes. The first book, published in 2016, covers the events from the earliest times until 1944, the second volume, which came out this year, deals with the events from 1945 to the present, while the third volume, which will be entirely dedicated to Serb-Albanian cultural ties, is nearly complete. Thus, this publication has already reached an impressive 900 pages, and will be considerably larger with the addition of the third volume.

I would briefly boil down the greatest significance of this book of encyclopedic scope and character to two key features:

To this day, this book has been and remains the only one that seeks to fully and in continuity describe Serb-Albanian relations from the earliest times to the present, in any language, and therefore it truly deserves our full attention and recognition. In the period between the first and the most recent edition, a series of publications devoted to this subject appeared, mainly collections of papers, as well as a series of books by foreign authors devoted mainly to Kosovo and the ethnic and political problems between the two nations. However, none of these books even attempted to offer what Imami's does - a comparative review, which follows the history of ethnic, historical and political relations between Serbs and Albanians from the arrival of the Slavs in the Balkans until today.

The second thing I would point out as very important, is that this book shows that Serbs and Albanians have lived for almost 1,500 years not next to each other but with each other, so that many regions of the Balkans were ethnically mixed until relatively recent times. In other words, before the creation of national programs and efforts to establish national and ethnic (pure) states, therefore, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, there was life together in the Balkans. Of course, along with challenges, occasional disagreements, personal quarrels, and in different political frameworks where Orthodox, Catholic or Muslim rulers dominated at different times, foreign or domestic masters, and so on. For better or worse, harder or easier, but there was life together. So our history is essentially a history of living together, not of being in a neighborhood.

A particular problem is - how to read this book - as a historical study, or a cultural review? The book certainly has historical pretensions and relies on a variety of historical sources, but in my opinion it is not standard history - Imami is not a professional historian, nor does he pretend to be one. He's not trying to do what historians as a rule do, delve deeply into the causes of events, judge historical figures and describe their motives. Generally he does not go into the question of the credibility of sources and authors cited, and often, he does not provide a general, broad context of events. Of course, in such a voluminous book, there will be exceptions to this approach, but in principle, his style is restrained, descriptive, impartial.

However, he's a conscientious author and his book is more reliable than many historical books that have been written in an extremely biased manner. All in all, I would say first and foremost that the book presents a cultural overview of Serb-Albanian relations, and in a way in which they are perceived through history, primarily from the Serb angle. Namely, his ambition is not to establish the historical truth, to consider an event from four or five different sources and expose a single, absolute truth. It is as if he is trying to completely, minutely mention, quote all possible Serb sources on certain events. For instance, when he talks about the crossing through Albania, or the Congress of Berlin and the expulsion of ethnic Albanians from the Toplica region, he cites statements by politicians, newspaper stories, memoirs of participants, all the way to military and diplomatic sources. No book is perfect, so of course one cannot expect the author to always be infallible in presenting such a comprehensive material. This relates primarily to the absence of a critical evaluation of the sources used. Thus, especially in the beginning, where the questions of the origin of the Albanian language, people and their original territory are considered, we find a multitude of quotations from various authors from various fields, which amount to different and mutually contradictory attitudes. It could be said that the author leaves it to the reader to make their own judgment; nevertheless, putting things into a context and considering the merits of somebody's claim would be very helpful to the reader. Academically inclined readers will also notice that plenty of quotations are given as a lump sum, without a clearly marked reference and page number of sources, which is also a prerequisite for use of historiographical material. And, finally, one could find mistakes in the book that a professional historian would not make - for example, the old thesis that Skanderbeg grew up as a converted Turk and a janissary in Istanbul, something that historians have long rejected as an unfounded myth. However, such errors are relatively few in such an erudite publication of encyclopedic volume.

Finally, we should point out to kind of dramaturgy and rhythm of the book. The closer it gets to the present, the more agonizing and difficult it is to read - to keep track of the growing hostility, ever more fierce and bloody conflicts, the growing political division and nationalist aspirations and, as if in a Shakespearian play - one is still not certain during the first few acts whether action will go toward tragedy or a happy end. Still, as we progress through time and events, it becomes clear there will be no happy ending. The book does not name someone to blame for such an outcome, nor is it the intention, but it leaves a bitter taste by providing introductions to a variety of actors that had led to this. However, it is important to point out that it pays special attention to those who, like the Serb leftists in the early 20th century, and many others, held a different view in relation to the official policy and clearly said that it was not too late to change the negative trend, and avoid hostility, clashes and mutual killings.

Imami's approach to controversial issues is not to overlook them, therefore, it is to write about them, but without sensationalism, soberly and impartially, as he usually does. However, the author's voice or comments exist in this book, and when we find them, we recognize what I would call the views of someone who believes in the closeness and friendship between Serbs and Albanians, and wishes them well equally. In those relatively rare, author's excursions, we find concise statements that sublimate long-term historical and life experiences. Thus, for instance, the author's phrase "Historically viewed, geographic 'natural borders' of nations represents a relative term" (volume I, p. 222) - could be taken as his summary, lapidary answer to the question about the historical right to Kosovo. A sum of the tragedy and the farce of our historical experience is also carried in the author's following lines:

"The historian Panta Sreckovic, a frequent companion of Yastrebov in Kosovo and Macedonia, recorded his words: 'In Kosovo, Serbs have lost an empire, in Kosovo will be the crucial battle to save the future of the Balkan Peninsula and the future of the Serb people.' (Indeed, this happened a hundred years later, in 1999, as a result of an aggressive policy towards Albanians in Kosovo led by the 'leader of the Serb people' in the late 20th century, Slobodan Milosevic. In an effort to create a final solution, he provoked the intervention of NATO, after which an ethnic demarcation line was drawn between Albanian and Serbian in Kosovo)." (Vol I, p. 165).

One could, therefore, read the ending of the book as an anticlimax, because we today, after 1,500 years of living together, for the first time - with small exceptions which present major problems - no longer live with each other and among each other, but next to each other. In the context of the rich and long historical, familial, tribal, customary and all other connections described by this valuable and versatile book, such an outcome can only be seen as failure.

Komentari 7

Pogledaj komentare