A revitalized far right in Serbia?

Tuesday, 12.10.2010.

23:06

A revitalized far right in Serbia? The rioters, however, mainly targeted government and media buildings and the headquarters of the pro-Western ruling party. The riots may have served as a wake-up call to the Serbian government that those neo-fascist groups could pose a threat to the ruling Serbian government and the wider Balkans. Belgrade was rocked by rioting Oct. 10 as ultranationalist neo-fascist groups battled police and law enforcement in the city for about seven hours. The pretense for the rioting was a gay pride parade, but rioters largely steered clear of the parade and targeted government buildings, state-owned media outlet RTS, and the headquarters of governing and pro-Western parties. The rioting came only two days before U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Belgrade on Oct. 12, a visit intended to reward the pro-Western Serbian government for recently showing flexibility in its approach toward the breakaway region of Kosovo, whose independence U.S. supports. Serbian ultranationalist parties and groups vehemently oppose Kosovo’s independence as well as the Serbian government’s EU integration efforts. The organizational capacity of the rioters demonstrated by the clashes suggests that the neo-fascist groups are better organized than the government believed prior to the rioting and that they are a viable threat to the stability of Serbia, and thus potentially the Western Balkans in their entirety. Around 6,500 members of neo-fascist groups took to the streets against around 5,600 police officers and gendarmes, elite Serbian Interior Ministry troops. Property was significantly damaged and around 200 people were injured, 147 of whom were police officers. The high proportion of police among the overall number injured suggests that police may have been hesitant to brutally clamp down on the rioters in order to avoid inciting a backlash, and thus more violence, but in doing so may have been unprepared for the intensity of the riots. Serbian law enforcement said it had arrested 249 people, 60 percent of whom are residents of interior Serbia, meaning that rioters came to Belgrade from surrounding towns. Serbian police said weapons were found on the roofs of some Belgrade buildings and that empty bullet casings were found in the ruling Democratic Party (DS) headquarters, which was one of the buildings targeted during the clashes. Serbian police also arrested the leader of the Obraz (“Cheek” in Serbian) neo-fascist movement on whose person they allegedly found plans for coordinating the riots and a list of orders for ultranationalist activists to attack different areas of the town. The Oct. 10 rioting seems to indicate that Serbia’s neo-fascist groups have become well-organized and present a serious threat to the state as they have become intertwined with traditional protest groups in Serbia. Generally referred to as “soccer hooligans” or just “hooligans,” the groups have played an important role in recent Balkan history. Composed of large groups of disaffected young men with nationalistic sympathies but no clear ideological leanings, soccer hooligans in both Croatia and Serbia were ideal recruits for paramilitary units of the Yugoslav Civil Wars in the 1990s. Serbian paramilitary volunteers who crisscrossed Bosnia-Herzegovina committing ethnic cleansing and looting property were a convenient tool for then-President Slobodan Milosevic because they offered Belgrade plausible deniability in terms of human rights violations while allowing Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina to take over areas in which other ethnicities had predominated. However, Milosevic lost the support of a wide array of nationalist groups in the late 1990s and soccer hooligans joined with pro-Western activists during the October 2000 revolution against the government. Hooligans this time provided much of the human mass that stormed government buildings on Oct. 5, helping usher a nominally pro-Western Serbia. The role of the soccer hooligans in the 2000 anti-Milosevic revolution illustrated to the much smaller neo-fascist groups the power that organized violence can have in Serbia. In the last ten years, an evolution of these groups has occurred and they now blend their membership with that of the infamous Serbian soccer hooligans. The hooligans are no longer relegated as guns for hire; they have an organizational capacity of their own under the umbrella of neo-fascist groups like Obraz, 1389 and Nasi (named for the pro-Kremlin Russian Nashi youth movement, from which they receive support). The neo-fascist groups, therefore, provide the hooligans and disaffected youth with the ideology and leadership they crave. The neo-fascist groups illustrated this organizational capacity on the streets of Belgrade during the drawn-out clashes, which were coordinated to spread thin the 5,600 police officers and prolong the mayhem for as long as possible. According to STRATFOR sources with considerable experience in anti-government protests in Belgrade, the rioters exhibited remarkable coordination in their attacks on “soft targets” around the town to continuously distract and dislocate law enforcement officials while staying well clear of the actual gay pride parade, which was heavily guarded. The sources also indicated the rioters knew exactly which avenues and streets in which they should concentrate their activities, allowing themselves ample maneuverability via side streets in case of a police counterattack. The groups had not previously been thought capable of this kind of discipline, which is usually drawn from strong leadership able to outline goals and enforce orders both before and during the riot, and thus control the violence in a way that seeks to accomplish its goals and steer the event throughout the day. An estimated 60 percent of the rioters were brought in from outside of Belgrade, showing an organizational capacity that extends beyond the capital with a network of operatives throughout Serbia. This is also symbolically important as it was only when activists were able to extend the movement beyond the large cities that anti-Milosevic protests became serious. The ability to organize a protest and recruit activists across the country also illustrates a competent level of funding. The danger for Serbia is that mainstream right-wing nationalist parties, which have recently had serious political setbacks, could seek to enlist the ultra-right wing movements for their energy and grassroots organizational abilities. Previous governments led by nationalist parties have referred to the right-wing movements as “Serbian youth” instead of as hooligans or rioters and excused events such as the burning of the U.S. Embassy in 2008 as an understandable expression of societal angst that can only be blamed on the West itself. One prominent member of the government at the time claimed that the West cannot complain about “a few broken windows when it destroyed our country.” The nationalist parties have a history of trying to co-opt elements of the neo-fascist groups and could try to do so again largely because they have never had real grassroots activists of their own — as is the case of the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) — or they have lost their own grassroots activists through the splintering of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), whose more popular spin-off, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), is now a pro-EU conservative party willing to work with the ruling DS. The political maturity of the established right-wing nationalist parties that have held power recently in post-Milosevic Serbia, coupled with the energy and capability of neo-fascist groups — at least one of which has the support of the pro-Kremlin Russian Nashi movement — could create a successful combination in Serbian politics. The current government is already facing setbacks on EU integration due to lack of European unity on approving Serbia’s candidacy as well as a severe economic crisis, both of which provide ample fuel for a rise of a new force in Serbian politics. The stability of the Serbian state is significant to the United States and European Union because the periodic convulsions of violence in the Balkans have long forced the rest of the world to pay attention. Indeed, a plea for stability is essentially the purpose of Clinton’s visit, as Washington has more pressing concerns to deal with in the Middle East, South Asia and the Russian resurgence. (Clinton has offered Washington’s symbolic support for Serbia’s EU integration but has not given Belgrade any concrete incentives to maintain the peace, which the United States largely does not have to offer.) However, the convenience and availability of outside powers are not a consideration for the Balkans when the region descends into violence, which very often means that Europe, the United States, Russia and Turkey can get drawn into its affairs whether they want to or not. And while in the 1990s the West may have had the luxury of intervening in the region for lack of opposing forces, namely Russia, the decade ahead may be considerably different, particularly when one considers the greater role that Turkey and Russia now play in the Balkans, and an ultranationalist Serbia could wreck havoc on European and U.S. priorities. This article s republished with permission of STRATFOR A masked rioter faces a police cordon (Tanjug) The Oct. 10 clashes in Belgrade demonstrated stronger-than-expected organizational capabilities on the part of ultranationalist neo-fascist groups, who are believed to have brought thousands of demonstrators from other parts of the country into the capital to riot during a gay pride parade. STRATFOR "The rioters exhibited remarkable coordination in their attacks on 'soft targets' around the town to continuously distract and dislocate law enforcement officials..."

A revitalized far right in Serbia?

The rioters, however, mainly targeted government and media buildings and the headquarters of the pro-Western ruling party. The riots may have served as a wake-up call to the Serbian government that those neo-fascist groups could pose a threat to the ruling Serbian government and the wider Balkans.Belgrade was rocked by rioting Oct. 10 as ultranationalist neo-fascist groups battled police and law enforcement in the city for about seven hours. The pretense for the rioting was a gay pride parade, but rioters largely steered clear of the parade and targeted government buildings, state-owned media outlet RTS, and the headquarters of governing and pro-Western parties.

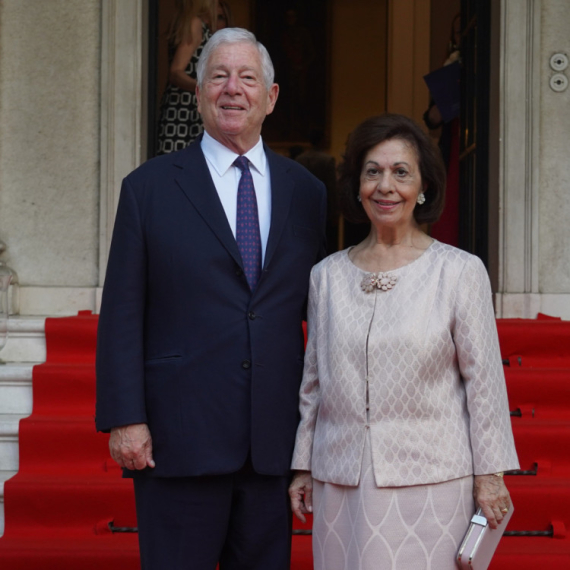

The rioting came only two days before U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Belgrade on Oct. 12, a visit intended to reward the pro-Western Serbian government for recently showing flexibility in its approach toward the breakaway region of Kosovo, whose independence U.S. supports.

Serbian ultranationalist parties and groups vehemently oppose Kosovo’s independence as well as the Serbian government’s EU integration efforts. The organizational capacity of the rioters demonstrated by the clashes suggests that the neo-fascist groups are better organized than the government believed prior to the rioting and that they are a viable threat to the stability of Serbia, and thus potentially the Western Balkans in their entirety.

Around 6,500 members of neo-fascist groups took to the streets against around 5,600 police officers and gendarmes, elite Serbian Interior Ministry troops. Property was significantly damaged and around 200 people were injured, 147 of whom were police officers.

The high proportion of police among the overall number injured suggests that police may have been hesitant to brutally clamp down on the rioters in order to avoid inciting a backlash, and thus more violence, but in doing so may have been unprepared for the intensity of the riots. Serbian law enforcement said it had arrested 249 people, 60 percent of whom are residents of interior Serbia, meaning that rioters came to Belgrade from surrounding towns.

Serbian police said weapons were found on the roofs of some Belgrade buildings and that empty bullet casings were found in the ruling Democratic Party (DS) headquarters, which was one of the buildings targeted during the clashes. Serbian police also arrested the leader of the Obraz (“Cheek” in Serbian) neo-fascist movement on whose person they allegedly found plans for coordinating the riots and a list of orders for ultranationalist activists to attack different areas of the town.

The Oct. 10 rioting seems to indicate that Serbia’s neo-fascist groups have become well-organized and present a serious threat to the state as they have become intertwined with traditional protest groups in Serbia. Generally referred to as “soccer hooligans” or just “hooligans,” the groups have played an important role in recent Balkan history.

Composed of large groups of disaffected young men with nationalistic sympathies but no clear ideological leanings, soccer hooligans in both Croatia and Serbia were ideal recruits for paramilitary units of the Yugoslav Civil Wars in the 1990s. Serbian paramilitary volunteers who crisscrossed Bosnia-Herzegovina committing ethnic cleansing and looting property were a convenient tool for then-President Slobodan Milosevic because they offered Belgrade plausible deniability in terms of human rights violations while allowing Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina to take over areas in which other ethnicities had predominated.

However, Milosevic lost the support of a wide array of nationalist groups in the late 1990s and soccer hooligans joined with pro-Western activists during the October 2000 revolution against the government. Hooligans this time provided much of the human mass that stormed government buildings on Oct. 5, helping usher a nominally pro-Western Serbia. The role of the soccer hooligans in the 2000 anti-Milosevic revolution illustrated to the much smaller neo-fascist groups the power that organized violence can have in Serbia.

In the last ten years, an evolution of these groups has occurred and they now blend their membership with that of the infamous Serbian soccer hooligans. The hooligans are no longer relegated as guns for hire; they have an organizational capacity of their own under the umbrella of neo-fascist groups like Obraz, 1389 and Nasi (named for the pro-Kremlin Russian Nashi youth movement, from which they receive support). The neo-fascist groups, therefore, provide the hooligans and disaffected youth with the ideology and leadership they crave.

The neo-fascist groups illustrated this organizational capacity on the streets of Belgrade during the drawn-out clashes, which were coordinated to spread thin the 5,600 police officers and prolong the mayhem for as long as possible. According to STRATFOR sources with considerable experience in anti-government protests in Belgrade, the rioters exhibited remarkable coordination in their attacks on “soft targets” around the town to continuously distract and dislocate law enforcement officials while staying well clear of the actual gay pride parade, which was heavily guarded.

The sources also indicated the rioters knew exactly which avenues and streets in which they should concentrate their activities, allowing themselves ample maneuverability via side streets in case of a police counterattack. The groups had not previously been thought capable of this kind of discipline, which is usually drawn from strong leadership able to outline goals and enforce orders both before and during the riot, and thus control the violence in a way that seeks to accomplish its goals and steer the event throughout the day.

An estimated 60 percent of the rioters were brought in from outside of Belgrade, showing an organizational capacity that extends beyond the capital with a network of operatives throughout Serbia. This is also symbolically important as it was only when activists were able to extend the movement beyond the large cities that anti-Milosevic protests became serious. The ability to organize a protest and recruit activists across the country also illustrates a competent level of funding.

The danger for Serbia is that mainstream right-wing nationalist parties, which have recently had serious political setbacks, could seek to enlist the ultra-right wing movements for their energy and grassroots organizational abilities. Previous governments led by nationalist parties have referred to the right-wing movements as “Serbian youth” instead of as hooligans or rioters and excused events such as the burning of the U.S. Embassy in 2008 as an understandable expression of societal angst that can only be blamed on the West itself.

One prominent member of the government at the time claimed that the West cannot complain about “a few broken windows when it destroyed our country.” The nationalist parties have a history of trying to co-opt elements of the neo-fascist groups and could try to do so again largely because they have never had real grassroots activists of their own — as is the case of the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) — or they have lost their own grassroots activists through the splintering of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), whose more popular spin-off, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), is now a pro-EU conservative party willing to work with the ruling DS.

The political maturity of the established right-wing nationalist parties that have held power recently in post-Milosevic Serbia, coupled with the energy and capability of neo-fascist groups — at least one of which has the support of the pro-Kremlin Russian Nashi movement — could create a successful combination in Serbian politics. The current government is already facing setbacks on EU integration due to lack of European unity on approving Serbia’s candidacy as well as a severe economic crisis, both of which provide ample fuel for a rise of a new force in Serbian politics.

The stability of the Serbian state is significant to the United States and European Union because the periodic convulsions of violence in the Balkans have long forced the rest of the world to pay attention. Indeed, a plea for stability is essentially the purpose of Clinton’s visit, as Washington has more pressing concerns to deal with in the Middle East, South Asia and the Russian resurgence. (Clinton has offered Washington’s symbolic support for Serbia’s EU integration but has not given Belgrade any concrete incentives to maintain the peace, which the United States largely does not have to offer.)

However, the convenience and availability of outside powers are not a consideration for the Balkans when the region descends into violence, which very often means that Europe, the United States, Russia and Turkey can get drawn into its affairs whether they want to or not. And while in the 1990s the West may have had the luxury of intervening in the region for lack of opposing forces, namely Russia, the decade ahead may be considerably different, particularly when one considers the greater role that Turkey and Russia now play in the Balkans, and an ultranationalist Serbia could wreck havoc on European and U.S. priorities.

This article s republished with permission of STRATFOR

Komentari 4

Pogledaj komentare