A critical month for Serbia…and the region

Sunday, 27.01.2008.

20:03

A critical month for Serbia…and the region — At a Council of Ministers Meeting on January 28, the EU will decide whether to invite Serbia to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) and whether at this time to authorize an EU Mission to Kosovo. — On February 3, the Second Round of elections for the Serbian Presidency will be held and the voters will choose between current President Boris Tadic and Tomislav Nikolic, the “caretaker” of the Radical Party. — Within a couple of weeks following the Serbian election, the Kosovo Albanians will issue their Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) and individual countries will begin to recognize it. The Serbian government will then respond. The sum total of all of the above will determine whether Serbia continues on a path (slowly or rapidly) towards integration into “Europe” or alternatively, becomes a “Belarus of the Balkans,” belligerently looking East instead of West and in some state of confrontation with the EU, the United States and its new “neighbor,” Kosovo. This may sound like it is too extreme a characterization, but unfortunately—and somewhat incredibly more than seven years after the fall of Milosevic—it is all too accurate. The Radical Party is the strongest in Serbia. It remains loyal to its extremist founder, Vojislav Seselj. It has never renounced the idea of a “Greater Serbia”; has consistently advocated extreme measures against any countries that recognize Kosovo’s independence; and has a political outlook totally antithetical to that of the EU. A Radical as President would make that office no longer a brake on extreme actions by elements of the Serbian government over Kosovo and turn it instead into a facilitator and exponent of such measures. Moreover, the recent statements by Prime Minister Kostunica and his party about the actions they will take in the case of the EU sending a mission to Kosovo to replace UNMIK or individual countries in the EU recognizing Kosovo independence should not be dismissed as empty threats. They mean it. Given the above, the EU is struggling to find ways to reinforce the pro-European elements in Serbia. They announced, for example, that technical talks on ways to relax visa restrictions on Serbian citizens would begin on January 30. They will postpone any decision on sending an EU Mission to Kosovo until after the Serbian Presidential elections. But they may well not be able to deliver on the most important element, the invitation to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement, at their January 28 Council of Ministers Meeting. Doing so would mean short-cutting normal procedures and abandoning the strict conditionality it has insisted upon with regard to the transfer to The Hague of Mladic and Karadzic. Belgium and the Netherlands are fiercely opposed to this step. Faced with the growing signs of a Nikolic victory, they may be persuaded either to give way or to permit the invitation to be issued with the specific stipulation that the necessary ratification by their governments would not take place until the extraditions were carried out. Failing that, the outcome of the January 28 meeting will probably be limited to a strong letter of encouragement to Serbia which gives full support to the visa discussions. This, however, will be of little use to the pro-European forces in Serbia. Without Prime Minister Vojislav Kostunica’s genuinely active support and endorsement, Boris Tadic has a steep uphill struggle to win the Presidency. Just recently Kostunica’s representatives outlined the concessions that Tadic would have to make to receive this support. The key point is that Tadic would have to formally agree that any decision by the EU to send a Mission to Kosovo would automatically abrogate the SAA. In other words, Kostunica seems determined to force the EU to choose between its plans for Kosovo and its relationship with Serbia. This is not simply rhetoric or a “negotiating position.” Tadic immediately rejected the conditionality, as to have accepted would have meant both abandoning one of the two main pillars of his campaign (the need to move closer to Europe) and losing his credibility and the foundation of his support within the Democratic Party and elsewhere. The end result is that more than ever before, the Presidential race is turning into a referendum as to which of two radically different directions Serbia will take in the coming years. Nikolic is significantly stronger this time than in the last Presidential elections in 2004. He, ironically, is the unlikely beneficiary of a growing level of disappointment of people in all walks of life over the post-Milosevic era. They are fed up with virtually all the political parties that have participated in the governments of the past seven years and are either apathetic and not voting or looking for change. Moreover, relations of Tadic and his Democratic Party with his logical supporters in the DSS (Kostunica), LDP (Jovanovic), and NS (Ilic) are also strained. Many will abstain from voting and some will certainly vote for Nikolic. And their support is vital for Tadic, if he is to overcome the 190,000 vote advantage Nikolic obtained in the first round. The only chance that Tadic has is to make the race even more clearly a Referendum on Serbia’s future and present in stark, specific terms to the electorate what a Radical victory would mean. He has to motivate voters not particularly sympathetic to him or his party to vote for him anyway for Serbia’s future If Nikolic wins as President, the UDI by the Kosovo Albanians will probably follow very soon thereafter. In any case, it will happen in a matter of weeks. The Serbian response will fall broadly into three categories: — Steps taken to fully preserve and assert its legal position and strong objections to the UDI. These include action at the UN, demarches to capitals, and establishing its physical presence in parts of Kosovo. — Steps taken to “punish” those countries and organizations which recognize Kosovo independence and “reward” those who continue to try to block it. This includes downgrading or breaking diplomatic relations; protests in front of Embassies; perhaps leaving the Partnership for Peace Program (since NATO is involved in Kosovo); Breaking Agreements with NATO over the transfer of troops between Bosnia and Croatia; and giving its oil industry to Russia in a sweetheart deal not subject to any sort of tender process. It will also take steps to “punish” Kosovo itself by isolating it and applying economic pressure. —Provocative steps in Kosovo to assert Serbian sovereignty deliberately designed to bring about confrontation both with the Kosovo government and with the International Organizations within Kosovo. This includes crossing “red lines” established by the International Community and publicly and privately made clear to everyone. From statements already made, my prediction is that Prime Minister Kostunica will insist on very strong, aggressive measures in all these areas. Naturally, having Nikolic as President will make it easier for him to do so. But in any case, I don’t see how this can end up in any way other than a breakdown in the ruling coalition, leading either to new Parliamentary elections or the formation of a government at least supported by the Radicals and absent the pro-European parties. There is no way that the DS and G17 Plus will be able to swallow the severity of measures which the Prime Minister seems more and more likely to initiate. Facilitator of extreme actions? Tomislav Nikolic (Beta) Serbia is now entering one of the most crucial months in its long history. A number of events will take place which will at the end of the day, determine Serbia’s path for the near and medium term future. These include: William Montgomery Kostunica seems determined to force the EU to choose between its plans for Kosovo and its relationship with Serbia. Tadic immediately rejected the conditionality, as to have accepted would have meant both abandoning one of the two main pillars of his campaign

A critical month for Serbia…and the region

— At a Council of Ministers Meeting on January 28, the EU will decide whether to invite Serbia to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) and whether at this time to authorize an EU Mission to Kosovo.— On February 3, the Second Round of elections for the Serbian Presidency will be held and the voters will choose between current President Boris Tadić and Tomislav Nikolić, the “caretaker” of the Radical Party.

— Within a couple of weeks following the Serbian election, the Kosovo Albanians will issue their Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) and individual countries will begin to recognize it. The Serbian government will then respond.

The sum total of all of the above will determine whether Serbia continues on a path (slowly or rapidly) towards integration into “Europe” or alternatively, becomes a “Belarus of the Balkans,” belligerently looking East instead of West and in some state of confrontation with the EU, the United States and its new “neighbor,” Kosovo.

This may sound like it is too extreme a characterization, but unfortunately—and somewhat incredibly more than seven years after the fall of Milošević—it is all too accurate. The Radical Party is the strongest in Serbia. It remains loyal to its extremist founder, Vojislav Šešelj. It has never renounced the idea of a “Greater Serbia”; has consistently advocated extreme measures against any countries that recognize Kosovo’s independence; and has a political outlook totally antithetical to that of the EU.

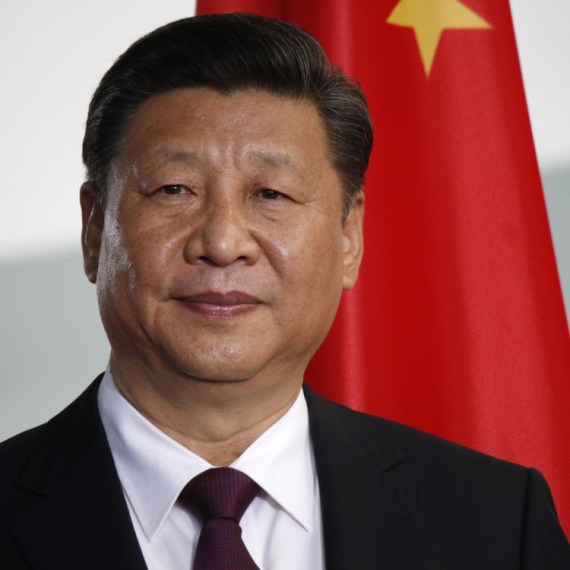

A Radical as President would make that office no longer a brake on extreme actions by elements of the Serbian government over Kosovo and turn it instead into a facilitator and exponent of such measures. Moreover, the recent statements by Prime Minister Koštunica and his party about the actions they will take in the case of the EU sending a mission to Kosovo to replace UNMIK or individual countries in the EU recognizing Kosovo independence should not be dismissed as empty threats. They mean it.

Given the above, the EU is struggling to find ways to reinforce the pro-European elements in Serbia. They announced, for example, that technical talks on ways to relax visa restrictions on Serbian citizens would begin on January 30. They will postpone any decision on sending an EU Mission to Kosovo until after the Serbian Presidential elections.

But they may well not be able to deliver on the most important element, the invitation to sign a Stabilization and Association Agreement, at their January 28 Council of Ministers Meeting. Doing so would mean short-cutting normal procedures and abandoning the strict conditionality it has insisted upon with regard to the transfer to The Hague of Mladić and Karadžić. Belgium and the Netherlands are fiercely opposed to this step.

Faced with the growing signs of a Nikolić victory, they may be persuaded either to give way or to permit the invitation to be issued with the specific stipulation that the necessary ratification by their governments would not take place until the extraditions were carried out. Failing that, the outcome of the January 28 meeting will probably be limited to a strong letter of encouragement to Serbia which gives full support to the visa discussions. This, however, will be of little use to the pro-European forces in Serbia.

Without Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica’s genuinely active support and endorsement, Boris Tadić has a steep uphill struggle to win the Presidency. Just recently Koštunica’s representatives outlined the concessions that Tadić would have to make to receive this support. The key point is that Tadić would have to formally agree that any decision by the EU to send a Mission to Kosovo would automatically abrogate the SAA.

In other words, Koštunica seems determined to force the EU to choose between its plans for Kosovo and its relationship with Serbia. This is not simply rhetoric or a “negotiating position.” Tadić immediately rejected the conditionality, as to have accepted would have meant both abandoning one of the two main pillars of his campaign (the need to move closer to Europe) and losing his credibility and the foundation of his support within the Democratic Party and elsewhere.

The end result is that more than ever before, the Presidential race is turning into a referendum as to which of two radically different directions Serbia will take in the coming years. Nikolić is significantly stronger this time than in the last Presidential elections in 2004. He, ironically, is the unlikely beneficiary of a growing level of disappointment of people in all walks of life over the post-Milošević era. They are fed up with virtually all the political parties that have participated in the governments of the past seven years and are either apathetic and not voting or looking for change.

Moreover, relations of Tadić and his Democratic Party with his logical supporters in the DSS (Koštunica), LDP (Jovanović), and NS (Ilic) are also strained. Many will abstain from voting and some will certainly vote for Nikolić. And their support is vital for Tadić, if he is to overcome the 190,000 vote advantage Nikolić obtained in the first round.

The only chance that Tadić has is to make the race even more clearly a Referendum on Serbia’s future and present in stark, specific terms to the electorate what a Radical victory would mean. He has to motivate voters not particularly sympathetic to him or his party to vote for him anyway for Serbia’s future

If Nikolić wins as President, the UDI by the Kosovo Albanians will probably follow very soon thereafter. In any case, it will happen in a matter of weeks. The Serbian response will fall broadly into three categories:

— Steps taken to fully preserve and assert its legal position and strong objections to the UDI. These include action at the UN, demarches to capitals, and establishing its physical presence in parts of Kosovo.

— Steps taken to “punish” those countries and organizations which recognize Kosovo independence and “reward” those who continue to try to block it. This includes downgrading or breaking diplomatic relations; protests in front of Embassies; perhaps leaving the Partnership for Peace Program (since NATO is involved in Kosovo); Breaking Agreements with NATO over the transfer of troops between Bosnia and Croatia; and giving its oil industry to Russia in a sweetheart deal not subject to any sort of tender process. It will also take steps to “punish” Kosovo itself by isolating it and applying economic pressure.

—Provocative steps in Kosovo to assert Serbian sovereignty deliberately designed to bring about confrontation both with the Kosovo government and with the International Organizations within Kosovo. This includes crossing “red lines” established by the International Community and publicly and privately made clear to everyone.

From statements already made, my prediction is that Prime Minister Koštunica will insist on very strong, aggressive measures in all these areas. Naturally, having Nikolić as President will make it easier for him to do so. But in any case, I don’t see how this can end up in any way other than a breakdown in the ruling coalition, leading either to new Parliamentary elections or the formation of a government at least supported by the Radicals and absent the pro-European parties. There is no way that the DS and G17 Plus will be able to swallow the severity of measures which the Prime Minister seems more and more likely to initiate.

Komentari 10

Pogledaj komentare