One rule for Jesus, another for Muhammad?

Friday, 16.03.2012.

16:38

One rule for Jesus, another for Muhammad? I've been thinking about this because of some media reaction to a conversation I had recently with Mark Thompson, the Director-General of the BBC, for our Oxford university project on free speech. After we talked about the BBC's broadcast of Jerry Springer: The Opera, which provoked angry protests from evangelical Christians because that satirical musical depicted Jesus as a petulant overgrown baby in a nappy, I put it to him that the BBC wouldn't dream of broadcasting something comparably satirical about the Prophet Muhammad. He replied 'I think essentially the answer to that question is yes'. This was picked up, first by the Daily Mail, then by the Daily Telegraph, the Spectator and at least one Christian website, with headlines such as 'BBC director general admits Christianity gets tougher treatment' and 'Should Christians kill Mark Thompson?' (Spectator). On Mail Online, a reader identifying him or herself as D. Acres of Balls Cross, West Sussex, posted the following comment 'This man is disgusting. He should be taken out and put up on a cross. That would teach him not to disrespect this country and its Christian faith.' Plainly a fine patriotic Christian, Mr or Mrs Outraged in Balls Cross. I suggested to Thompson that this asymmetry in the way broadcasters (not just the BBC, and not just in Britain) treat Islam as compared with other belief systems was a result of the threat of violence from Muslim extremists. He replied: 'Well clearly it's a very notable move in the game... "I complain in the strongest possible terms" is different from "I complain in the strongest possible terms and I'm loading my AK47 as I write".' That's a frank acknowledgment of one of the biggest threats to free speech around the world today. Classic American free speech literature talks of 'the heckler's veto'. These days, we face the assassin's veto. Such violent intimidation must always be resisted. To yield to it ultimately encourages others to threaten violence themselves. If only we atheists and Christians were credibly thought to be loading our AK47s, more 'respect' might mysteriously follow. But in his very thoughtful response, Thompson mentioned two other reasons for asymmetric treatment. First, whereas Christianity is the 'broad-shouldered' established religion of the majority in Britain, Islam is that of vulnerable ethnic minorities, 'who may already feel in other ways isolated, prejudiced against, and where they may well regard an attack on their religion as racism by other means'. Second, speaking as a practising Christian himself, Thompson said that you have to understand the emotional force of 'what blasphemy feels like to someone who is a realist in their religious belief'. Religious beliefs cannot simply be compared with rational, propositional statements, such as 2 + 2 = 4. Indeed, 'to a Muslim and potentially also to a Christian, there are certain as it were quasi-blasphemous things or blasphemous things that could be said which would themselves feel to them very like a threat of violence'. Now, to be clear, I don't think these two further arguments justify the asymmetry. I think the BBC should feel free to air something equally satirical in relation to Islam - which, by the way, would not really be satirical about the religion, since Jerry Springer: The Opera was a satire on the Jerry Springer show and American popular culture, not on Jesus Christ or Christianity. And I do think the main reason the BBC, and most other media, are more nervous around Islam is the threat of violence. Yet his two other arguments deserve to be engaged with seriously, and they both ultimately come back to equality. It is not self-evidently wrong or illiberal to suggest that members of disadvantaged minorities should be treated with special sensitivity. Equality does not mean, for example, that Oxford university admissions interviewers, when confronted with two candidates, one the son of poor immigrants who has struggled up through a failing comprehensive school, the other the Etonian son of a millionaire, should say: well, Sunder has worse exam grades and performed worse at interview so obviously we must admit David. So the right questions here are: is it true that Muslims still constitute a vulnerable, disadvantaged minority in the UK? (To complicate things further, that might be true in aggregate, but not in some individual cities.) And if so, is this the right way in which to display special sensitivity? His point about the special character of religious beliefs also brings us back to equality. Empirically speaking, it is undoubtedly true that many people care especially strongly about their religious beliefs. But those are not sufficient grounds on which to privilege faith over reason. Suppose I feel as passionately about the scientific reality of evolution as literalist Christians or Muslims do about creation. Why should public policy or a public service broadcaster protect their feelings more than mine? Britain's Equality Act suggests they should not, with this glorious definitional contortion: 'Belief means any religious or philosophical belief and a reference to belief includes a reference to a lack of belief'. Difficult though it is, we must never abandon the quest for equal liberty under law. Everyone is entitled to what the philosopher Ronald Dworkin calls 'equal respect and concern'. That does not mean treating everyone exactly the same in every circumstance. But whenever you hear anyone (including me or you) arguing for unequal treatment of any kind, shine the searchlight and take a closer look. The same evangelical Christian who complains of unequal treatment from the BBC will vociferously oppose gay marriage. The same European liberal who argues passionately that newspapers should be free to publish cartoons of Muhammad will defend laws criminalising genocide denial. Double standards are the warning signals of a free society. Timothy Garton Ash is Professor of European Studies at Oxford University, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and the author, most recently, of Facts are Subversive: Political Writing from a Decade Without a Name Simple things can be so difficult. Take equality, for example. Britain now has an Equality Act, to promote that good thing. But when you start looking at what it means in practice, matters gets more complicated. Timothy Garton Ash "Simple things can be so difficult. Take equality, for example. Britain now has an Equality Act, to promote that good thing. But when you start looking at what it means in practice, matters gets more complicated."

One rule for Jesus, another for Muhammad?

I've been thinking about this because of some media reaction to a conversation I had recently with Mark Thompson, the Director-General of the BBC, for our Oxford university project on free speech. After we talked about the BBC's broadcast of Jerry Springer: The Opera, which provoked angry protests from evangelical Christians because that satirical musical depicted Jesus as a petulant overgrown baby in a nappy, I put it to him that the BBC wouldn't dream of broadcasting something comparably satirical about the Prophet Muhammad. He replied 'I think essentially the answer to that question is yes'.This was picked up, first by the Daily Mail, then by the Daily Telegraph, the Spectator and at least one Christian website, with headlines such as 'BBC director general admits Christianity gets tougher treatment' and 'Should Christians kill Mark Thompson?' (Spectator). On Mail Online, a reader identifying him or herself as D. Acres of Balls Cross, West Sussex, posted the following comment 'This man is disgusting. He should be taken out and put up on a cross. That would teach him not to disrespect this country and its Christian faith.' Plainly a fine patriotic Christian, Mr or Mrs Outraged in Balls Cross.

I suggested to Thompson that this asymmetry in the way broadcasters (not just the BBC, and not just in Britain) treat Islam as compared with other belief systems was a result of the threat of violence from Muslim extremists. He replied: 'Well clearly it's a very notable move in the game... "I complain in the strongest possible terms" is different from "I complain in the strongest possible terms and I'm loading my AK47 as I write".' That's a frank acknowledgment of one of the biggest threats to free speech around the world today. Classic American free speech literature talks of 'the heckler's veto'. These days, we face the assassin's veto. Such violent intimidation must always be resisted. To yield to it ultimately encourages others to threaten violence themselves. If only we atheists and Christians were credibly thought to be loading our AK47s, more 'respect' might mysteriously follow.

But in his very thoughtful response, Thompson mentioned two other reasons for asymmetric treatment. First, whereas Christianity is the 'broad-shouldered' established religion of the majority in Britain, Islam is that of vulnerable ethnic minorities, 'who may already feel in other ways isolated, prejudiced against, and where they may well regard an attack on their religion as racism by other means'.

Second, speaking as a practising Christian himself, Thompson said that you have to understand the emotional force of 'what blasphemy feels like to someone who is a realist in their religious belief'. Religious beliefs cannot simply be compared with rational, propositional statements, such as 2

+ 2 = 4. Indeed, 'to a Muslim and potentially also to a Christian, there are certain as it were quasi-blasphemous things or blasphemous things that could be said which would themselves feel to them very like a threat of violence'.

Now, to be clear, I don't think these two further arguments justify the asymmetry. I think the BBC should feel free to air something equally satirical in relation to Islam - which, by the way, would not really be satirical about the religion, since Jerry Springer: The Opera was a satire on the Jerry Springer show and American popular culture, not on Jesus Christ or Christianity. And I do think the main reason the BBC, and most other media, are more nervous around Islam is the threat of violence.

Yet his two other arguments deserve to be engaged with seriously, and they both ultimately come back to equality. It is not self-evidently wrong or illiberal to suggest that members of disadvantaged minorities should be treated with special sensitivity. Equality does not mean, for example, that Oxford university admissions interviewers, when confronted with two candidates, one the son of poor immigrants who has struggled up through a failing comprehensive school, the other the Etonian son of a millionaire, should say: well, Sunder has worse exam grades and performed worse at

interview so obviously we must admit David. So the right questions here are: is it true that Muslims still constitute a vulnerable, disadvantaged minority in the UK? (To complicate things further, that might be true in aggregate, but not in some individual cities.) And if so, is this the right way in which to display special sensitivity?

His point about the special character of religious beliefs also brings us back to equality. Empirically speaking, it is undoubtedly true that many people care especially strongly about their religious beliefs. But those are not sufficient grounds on which to privilege faith over reason. Suppose I feel as passionately about the scientific reality of evolution as literalist Christians or Muslims do about creation. Why should public policy or a public service broadcaster protect their feelings more than mine? Britain's Equality Act suggests they should not, with this glorious definitional contortion: 'Belief means any religious or philosophical belief and a reference to belief includes a reference to a lack of belief'.

Difficult though it is, we must never abandon the quest for equal liberty under law. Everyone is entitled to what the philosopher Ronald Dworkin calls 'equal respect and concern'. That does not mean treating everyone exactly the same in every circumstance. But whenever you hear anyone (including me or you) arguing for unequal treatment of any kind, shine the searchlight and take a closer look. The same evangelical Christian who complains of unequal treatment from the BBC will vociferously oppose gay marriage. The same European liberal who argues passionately that newspapers should be free to publish cartoons of Muhammad will defend laws criminalising genocide denial. Double standards are the warning signals of a free society.

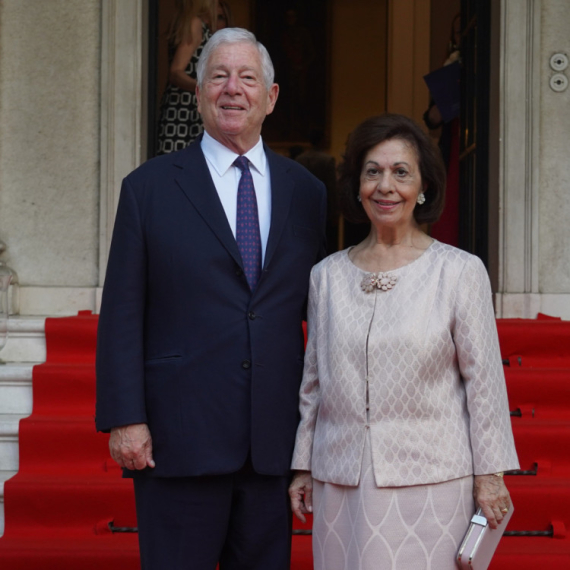

Timothy Garton Ash is Professor of European Studies at Oxford University, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and the author, most recently, of Facts are Subversive: Political Writing from a Decade Without a Name

Komentari 6

Pogledaj komentare