At Davos, small economies calling bigger shots

At Davos, world leaders called for a new economic agenda in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Friday, 29.01.2010.

17:37

At Davos, world leaders called for a new economic agenda in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Their demands reflected the growing recognition that a new world order is taking shape. At Davos, small economies calling bigger shots As emerging nations edge up the political ladder to challenge the hegemony once held by Europe and the United States, they are exerting more influence on the annual meeting of global political and business powers in Davos, Switzerland, than ever before. And their presence isn't just being felt at the edges of the debate. In a speech late Thursday, South Korean President Lee Myung-bak - leader of the G20 group of nations this year - called for a "post-crisis agenda" that would lead to sustainable growth while avoiding a new financial or economic crisis. His sentiment echoed that of French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who opened the conference earlier this week with a speech slamming the international banking community for its role in the global financial meltdown. Their comments - challenging the banking system and other entrenched seats of power - reflect stark changes in the annual alpine pow-wow, now in its 40th year. Davos is no longer just a place for the Western wealthy to push their agendas, observers note. Brazil, Russia, India and China, known as the BRIC nations, as well as other growing economies, have more of a say than ever there. "If anyone in Davos these days asks where the epicenter of growth is going to be in the coming years, they get a single answer: emerging economies," German business journalist Dieter Fockenbrock wrote in recent column for the Handelsblatt newspaper. The BRIC nations have boosted their share of the global capital markets from 1.4 percent to 15 percent in the past 10 years - more than a tenfold increase, according to Fockenbrock. And attendance at Davos from BRIC countries has more than doubled since 2005, up to about 10 percent of the participants this year. German economist Michael Braeuninger, of the Hamburg Institute of International Economics, agreed that there is "definitely something like a new world order" in place, but, he adds, it's "a process that has been running for some time now." That process is reflected not only in Davos but other policy epicenters, like the Group of 20. That powerful coalition comprises BRIC countries and many more, like South Africa and Argentina - and they've earned their spot at the table, Braeuninger told Deutsche Welle. Global financial crises used to stem from the weaker parts of the developing world - think of the old trope of the Latin American debt crisis. But in the latest economic meltdown, it was the US and other advanced countries who suffered most. "Within the economic crisis (Brazil, Russia, India and China) did a lot to stabilize the world economy. So they have showed themselves as economic and political powers," Braeuninger said. And UC Berkeley economics professor Barry Eichengreen told the New York Times that the economic crisis has given people in emerging markets "a new confidence to assert the agenda for reform." "The days are past when US and Europeans would make all the proposals," he said. Most observers acknowledge that Europe is at a greater risk of losing relevancy than the US is; even though it was hard hit by the economic crisis, its sheer size and economic power grant it continued hegemony, observers say. "Logic says that as the US retains, and emerging economies attain, leadership through unhampered growth, Europe will fall between the cracks," Fockenbrock wrote in Handelsblatt. He worries that companies from Germany, France and Great Britain could "get crushed between the giant economies of the USA and China." And indeed, Europe has been essentially kneecapped by the global economic crisis, while the US - which represents a full 20 to 25 percent of the world economy - is often said to be finding its way to recovery. "In absolute levels the US is still the most important world economy," said Braeuninger. "Of course, if you think about the rate of growth and change, then China gains a lot." Meanwhile, Braeuninger warned about a false logic that could lead people to think that a rise in economic power in one bloc means an automatic drop in welfare for another. But economics is not a zero-sum game, he says. "It is important not to think in terms of one country losing and another one winning," he said. "It is important to think that if we increase trade between countries, then both countries gain." Participants gather in the main lobby at the World Economic Forum in Davos (Beta/AP)

At Davos, small economies calling bigger shots

As emerging nations edge up the political ladder to challenge the hegemony once held by Europe and the United States, they are exerting more influence on the annual meeting of global political and business powers in Davos, Switzerland, than ever before.And their presence isn't just being felt at the edges of the debate. In a speech late Thursday, South Korean President Lee Myung-bak - leader of the G20 group of nations this year - called for a "post-crisis agenda" that would lead to sustainable growth while avoiding a new financial or economic crisis.

His sentiment echoed that of French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who opened the conference earlier this week with a speech slamming the international banking community for its role in the global financial meltdown.

Their comments - challenging the banking system and other entrenched seats of power - reflect stark changes in the annual alpine pow-wow, now in its 40th year.

Davos is no longer just a place for the Western wealthy to push their agendas, observers note. Brazil, Russia, India and China, known as the BRIC nations, as well as other growing economies, have more of a say than ever there.

"If anyone in Davos these days asks where the epicenter of growth is going to be in the coming years, they get a single answer: emerging economies," German business journalist Dieter Fockenbrock wrote in recent column for the Handelsblatt newspaper.

The BRIC nations have boosted their share of the global capital markets from 1.4 percent to 15 percent in the past 10 years - more than a tenfold increase, according to Fockenbrock. And attendance at Davos from BRIC countries has more than doubled since 2005, up to about 10 percent of the participants this year.

German economist Michael Braeuninger, of the Hamburg Institute of International Economics, agreed that there is "definitely something like a new world order" in place, but, he adds, it's "a process that has been running for some time now."

That process is reflected not only in Davos but other policy epicenters, like the Group of 20. That powerful coalition comprises BRIC countries and many more, like South Africa and Argentina - and they've earned their spot at the table, Braeuninger told Deutsche Welle.

Global financial crises used to stem from the weaker parts of the developing world - think of the old trope of the Latin American debt crisis. But in the latest economic meltdown, it was the US and other advanced countries who suffered most.

"Within the economic crisis (Brazil, Russia, India and China) did a lot to stabilize the world economy. So they have showed themselves as economic and political powers," Braeuninger said.

And UC Berkeley economics professor Barry Eichengreen told the New York Times that the economic crisis has given people in emerging markets "a new confidence to assert the agenda for reform."

"The days are past when US and Europeans would make all the proposals," he said.

Most observers acknowledge that Europe is at a greater risk of losing relevancy than the US is; even though it was hard hit by the economic crisis, its sheer size and economic power grant it continued hegemony, observers say.

"Logic says that as the US retains, and emerging economies attain, leadership through unhampered growth, Europe will fall between the cracks," Fockenbrock wrote in Handelsblatt. He worries that companies from Germany, France and Great Britain could "get crushed between the giant economies of the USA and China."

And indeed, Europe has been essentially kneecapped by the global economic crisis, while the US - which represents a full 20 to 25 percent of the world economy - is often said to be finding its way to recovery.

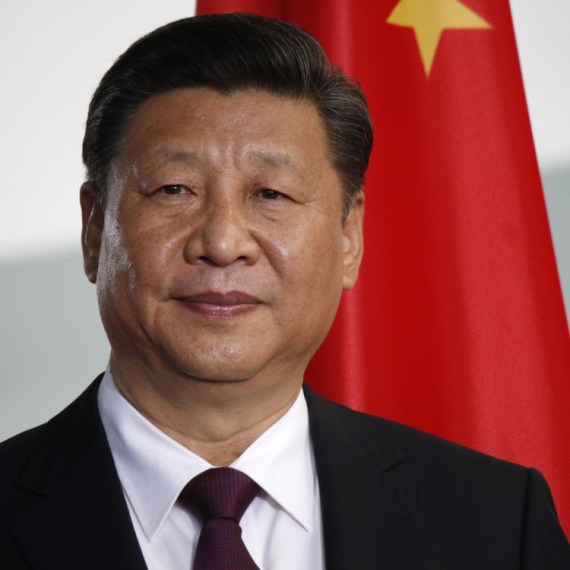

"In absolute levels the US is still the most important world economy," said Braeuninger. "Of course, if you think about the rate of growth and change, then China gains a lot."

Meanwhile, Braeuninger warned about a false logic that could lead people to think that a rise in economic power in one bloc means an automatic drop in welfare for another. But economics is not a zero-sum game, he says.

"It is important not to think in terms of one country losing and another one winning," he said. "It is important to think that if we increase trade between countries, then both countries gain."

Komentari 1

Pogledaj komentare